In a stark contrast to the hype that surrounded President William Ruto’s much-publicized nationwide livestock vaccination campaign towards the end of last year, talk about the initiative seems hushed.

Questions are emerging about the government’s preparedness to execute the ambitious project, which has attracted widespread criticism.

Veterinary doctors are sounding the alarm over logistical hurdles as government officials and UDA politicians remain conspicuously silent.

The campaign, a flagship initiative unveiled by President Ruto in late 2024, aims to vaccinate 21 million cattle and 50 million sheep and goats. Critics, however, question Kenya’s capacity to execute such an ambitious undertaking.

“Last year, we vaccinated 700,000 livestock in Kitui and 800,000 in Wajir. It’s a continuous exercise,” said Dr. Allan Azegele, Director of Veterinary Services, during an interview on December 23.

Although Azegele portrays the campaign as an extension of ongoing efforts, stakeholders argue that a national rollout demands much more robust planning.

A key webinar meeting held on December 16 between the Kenya Veterinary Association (KVA) and government officials highlighted the critical gaps in preparedness. The meeting, which included representatives from the Kenya Veterinary Vaccines Production Institute (Kevevapi) and other stakeholders, ended without a clear resolution.

KVA Chairperson Kelvin Osore criticised the government for failing to present a detailed plan.

“Our position is clear: the vaccination exercise should be postponed until a comprehensive roadmap and calendar for civic engagement are provided,” KVA stated in a memo to its members.

Among KVA’s demands are increased funding, expanded production capacity at Kevevapi, and the recruitment of additional veterinary officers. Currently, Kevevapi can only produce and store 13 million vaccine doses annually, far short of the 144 million doses required for the campaign. Adding to the strain is a prior commitment to supply Uganda with three million doses by mid-2025.

“The challenge isn’t just producing the vaccines,” said Osore. “We also need sufficient storage facilities, more trained personnel, and an efficient distribution system to ensure vaccines are used before they expire.”

The National Treasury report reveals no funding for national livestock vaccination programme, despite a public promise and the State Department of Livestock’s request for Sh4.6 billion in the 2024 budget.

“Continued losses attributed to these priority livestock trans-boundary animal diseases of great economic importance in terms of mortality, morbidity and restricted market access are enormous. Non-implementation will also imply total disregard to a presidential directive to undertake national vaccination,” reads the department report.

The programme, which aims to combat foot-and-mouth disease and peste des petits ruminants, which threaten Kenya’s livestock and export market. The five-year initiative, costing Sh21 billion, plans to vaccinate 22 million cattle and 50 million goats.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

“We met with governors, and this will be a continuous program,” Azegele said.

KVA has also called for the recruitment and salary harmonization of veterinary officers, insisting their compensation should match that of medical officers, given the similar risks they face.

“The government should commit in writing to harmonize salaries. Without proper compensation, we risk losing crucial personnel,” warned Osore.

KVA has also demanded clarity on its role in implementing the campaign.

“Veterinary departments must be equipped with vehicles, cold storage units, and adequate manpower,” Osore emphasized, adding that the safety of vaccination teams must be prioritized, particularly in remote and conflict-prone regions.

KVA Chairperson underscored the need for civic engagement to build support among farmers and stakeholders since public trust remains another major concern.

“This isn’t just about administering vaccines. It’s about ensuring farmers understand and trust the process, and making them have all relevant information to assure them that the livestock, which is their investment, is safe,” he noted.

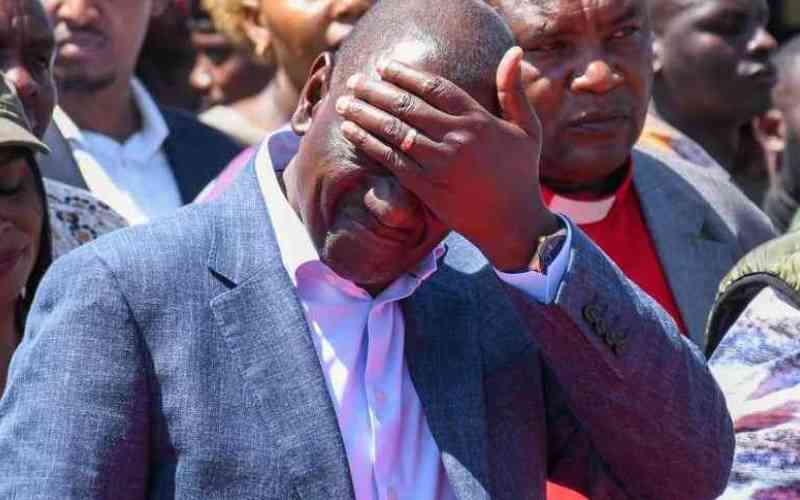

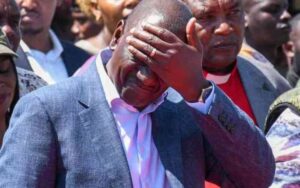

Despite mounting criticism, President Ruto stood firm in November, where he said at the Kimalel Goat Auction in Baringo County on December 17, he defended the campaign, emphasizing its potential to improve livestock health and boost Kenya’s international trade prospects.

“We are determined to carry out this program to enhance livestock prices and meet global market standards,” said Ruto, adding, “Anybody opposing vaccination to eliminate FMD and PPR is simply mad and unreasonable and possibly stupid,” Ruto said.

However, during a visit to Kilgoris a week earlier, the president appeared to soften his stance, suggesting that participation in the campaign would be voluntary. Dr Azegele later clarified that the campaign would prioritize regions most affected by disease outbreaks.

“For cattle, we’ll focus on areas battling foot-and-mouth disease, such as the highlands, Western, and Central Kenya. For sheep, we’ll target Arid and Semi-Arid plagued by Peste des Petits Ruminants (PPR),” Azegele explained.

He assured stakeholders that Kenya has ten laboratories in Nairobi, Kericho, Mariakani, and Nakuru equipped to store the vaccines under the required cold temperature, which is expected to span two years.

“Eliminating these diseases will unlock new markets and increase the value of our meat exports,” Dr Azegele added.

In an interview with The Standard, Kevevapi managing director Alex Sabuni, said the institute has been producing vaccines for more than three decades and supplying to different countries in Africa. Outside Kenya, its largest market is Uganda, but he added that “we have supplied the vaccines all the way to West Africa, with most recent markets being Mali and Senegal and we have also supplied UAE.”

Veterinary professionals warn that launching the campaign without addressing key issues could jeopardise its success.

“We are ready to collaborate with the government, but only under conditions that guarantee the program’s effectiveness, educate Kenyans about the vaccine, and involve all stakeholders for transparency,” Osore stressed.

Speaking to The Standard, KVA Chairperson said the government requires cold storage facilities at county headquarters and more veterinary officers. He reiterated that KVA was calling for a postponement, citing critical gaps in funding, logistics, and infrastructure that threaten the program’s success.

“We support government efforts to roll out national vaccination campaigns, but our support for this specific program is contingent on addressing these key issues,” Osore told The Standard.

Dr Azegele, director for veterinary services, said the vaccination programme would take a risk-based approach, starting off with high-risk areas, especially dairy zones.

“This is a critical disease control measure that is geared towards protecting our animals from these two diseases that have a great economic impact and also affect our access to markets. We will be rolling it out in January,” he said.

“We will take a risk-based approach. Foot and mouth has devastating effects on the dairy herd, and we have counties that are predominantly dairy producers. That is where we are going to focus our initial approach for control of foot and mouth,” he added.

“Our ultimate target is to have recognition of freedom from foot and mouth disease. The vaccination will be done twice a year. The current vaccine confers immunity for about six months. If we are able to undertake the vaccination twice a year for about three years, we will be able to seek freedom from this disease and once we are recognised by the World Organisation for Animal Health, the world will be open to us. We will be able to demonstrate that our herd is free of foot and mouth.”

The government has yet to explain how it plans to fund, produce, store, and distribute the 144 million vaccine doses needed annually. “We are not opposed to vaccination campaigns, but this one is ill-prepared and as professionals we cannot be part of a program where our clients cannot trust us,” Osore said.

Officials from KVA highlighted Kevevapi’s limited capacity as a major bottleneck. KEVEVAPI, the region’s largest vaccine manufacturer, can only produce 13 million doses annually, leaving a significant shortfall. “Uganda has requested three million doses by June 2025. As it stands, Kevevapi can only handle an additional 10 million doses, which is insufficient,” an official told The Standard.

Veterinary doctors further noted that the absence of a budget for the campaign raises questions about its feasibility. They outlined several conditions that must be met before the program can proceed, including clear plans for capacity enhancement at Kevevapi and increased staffing.

“The government must ensure that veterinary officers’ salaries and allowances are harmonized with those of medical officers. This includes aligning stipends for interns, as both groups face similar risks,” Osore said asking politicians to keep off vaccination process so that the professionals can run it comfortable since the public trusts professionals.

He also emphasized the need for a written commitment from the government to involve KVA in the program’s execution. “Counties need resources such as cold storage facilities, vehicles, and personnel to carry out the exercise effectively. Security for vaccination teams must also be guaranteed,” Osore added.

KVA has called for nationwide civic engagement to secure public trust. Without proper consultation, Osore warned, the campaign could fail.

“This is not just about injecting animals with vaccines; it’s about building trust among farmers and stakeholders. Public participation is essential,” he said, adding, “We all agree that vaccinations are vital, but the way this is being handled leaves much to be desired.”

For now, veterinary doctors stand firm: “This program must be done the right way, or not at all,” Osore said.