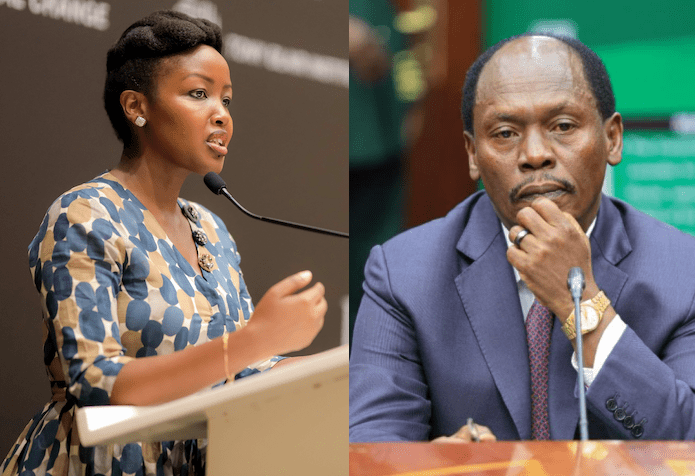

By the time Martha Karua sat for her O-Levels, she had switched schools severally. In all instances, she’d stood up for her rights as a student, and questioned unjust conventions and unfair norms condoned by students.

At Kiburia Girls she had been asked to uproot a stump as a punishment for “making noise” and she declined. In another school she was ordered to bend over so she could be caned, and she said nyet! and took off for the school gate.

In her final year in Karoti Girls, she took on the headmistress for humiliating her and denounced her as her teacher. For this, she had to contend with studying from home for five months, and preparing for the final exams on her own, and commuting 25 kilometers daily, to sit her exams.

For all the troubles she’d gone through in Kirinyaga, she passed with flying colors, and proceeded to Nairobi Girls for her A-Levels. She never looked back and took this rebellious streak with her to the Seventh parliament.

The return to multiparty politics in 1991, and the General Election of the following year, did not usher in the much-anticipated change in governance.

The divisions in the ranks of the Opposition handed President Moi victory. President Moi’s government continued with its tactics of repression, this time directed at the Opposition both in and out of Parliament.

Although the freedoms of association and assembly were provided for in the Constitution, the Kanu government continued to curtail these and other fundamental freedoms.

Administrative roadblocks were erected illegally to curtail the Opposition’s interaction with the masses.

This gave birth to the clamour for overhauling of the Constitution and repealing all oppressive laws, some of which were relics of the colonial order. The Opposition working closely with the civil society demanded constitutional and legal reforms ahead of the 1997 General Election, thus raising tension between the two opposing sides.

The Opposition and civil society groups, including religious organisations, met regularly at Ufungamano House, which had become a refuge for dissenting voices. Many establishments at the time, out of fear of rubbing the government the wrong way, would not readily allow dissenting voices to literally camp in their premises.

The Ufungamano group was led by the National Convention Execute Council (NCEC), a civil society group spearheading constitutional review.

Their mantra was “no reforms, no elections”. Apart from key Opposition leaders, a good number of luminaries in Parliament attended these meetings. I, however, did not join the Ufungamano talks, although I agreed with their demand for reforms before the upcoming general election.

I felt that as parliamentarians, we needed to use our space in Parliament to help the country out of the prevailing national crisis.

Demonstrations organised by the Ufungamano group would be routinely dispersed through the use of excessive force by the police. The situation was threatening to get out of hand.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

In response to the rising tension in June 1997, I together with a bipartisan group of Members of Parliament who included Jillo Falana, then-member for Saku Constituency; and George Anyona, then-member for Kitutu Chache; formed the Inter-Parties Parliamentary Group (IPPG).

Our purpose was to negotiate constitutional and legal changes that were deemed necessary before that year’s general election.

The IPPG meetings quickly attracted the support of many parliamentarians from both the Opposition and the Government.

Soon, we were given live coverage by the national broadcaster, KBC, an indication that the Government had warmed up to this idea, which was literally a lifeline from the developing national crisis.

Parliamentarians from the government side reported progress to President Moi daily and got his blessings at every stage. The progress achieved was known to all and sundry, courtesy of the live broadcasts.

We in the Opposition did not initially consult our party leaders, but we knew what the Opposition demands for minimum reforms were and used this as the basis for our negotiations.

Within a few days of the IPPG talks and the progress of the reform agenda, the tension that was simmering countrywide was diffused and all eyes were now on the IPPG talks.

We literally pulled the rag from under the feet of the Ufungamano group. Colleagues who had aligned themselves with Ufungamano started streaming back to Parliament. For IPPG to succeed, we needed the support of the majority, if not all Members of Parliament.

Though I was poised to co-chair the constitutional, Legal and Administrative Reforms Committee with Dalmas Otieno of Kanu, I ceded the space to Kiraitu Murungi of the FORD Kenya party and member for Imenti South constituency.

He was one of the early arrivals to IPPG from Ufungamano, and I proposed him as co-chair.

There were two other committees of the IPPG, namely the Peace and Security Committee, and the Electoral Reforms Committee, which had Phoebe Asiyo and Agnes Ndetei respectively as the sole female members.

Our committee achieved a host of reforms, among them the repeal of the offence of sedition and the repeal of the Chiefs’ Authority Act, a colonial relic that gave oppressive powers to local administrators that could be used to even stop a family get-together.

We also made it mandatory by law for the national broadcaster to give equal airtime to both government and Opposition candidates during campaigns.

We proposed constitutional amendments to provide for the sharing of slots to nominate members both in Parliament and in Local Authorities between the Government and Opposition in proportion to their respective numbers in Parliament. Further, we outlawed discrimination based on gender.

The colonial era requirement of a permit from the administration to hold public gatherings was also repealed.

These were among the many legal and constitutional amendments that we believed would greatly level the playing field for all candidates. Until then, the odds were hugely stacked in favour of the government and its preferred candidates.

The success of the IPPG talks was mainly due to the willingness of the government side to cede ground on key issues.

Indeed, President Moi and those in his inner circle realised that IPP offered him and Kanu a political lifeline because our talks eased the political tensions across the country. Parliament, under Speaker Francis Kaparo, facilitated our sittings within its precincts, although the IPPG was not an official parliamentary committee, but a members’ informal initiative.

The failure of the opposition to unite once again cost us victory in 1997, giving President Moi his second and final term under the 1992 constitutional amendments.

Having emerged first runner-up in 1997. Mr Kibaki became the Leader of the Official Opposition, succeeding Mr Matiba, who had taken up the position after finishing second in the 1992 election.

I was the DP elected National Secretary for Legal and Constitutional Ali from 1993 and thus, the spokesperson for the party on all legal matters. The expectation then was that I would be the automatic shadow Attorney-General (AG) when Kibaki formed his shadow cabinet.

It came as a surprise when Mr Kibaki overlooked me and appointed a new entrant to the DP Party, Mr Kiraitu Murungi, as the shadow AG while appointing me as shadow minister for Culture and Social Services.

Mr Murungi’s appointment as shadow AG conflicted with my elected position as National Secretary for Legal and Constitutional Affairs.

It opened the possibility of conflicting decisions on legal issues by having both of us as the party’s spokespersons on legal matters.

Mr Kibaki was following President Moi’s script, the latter having appointed Mrs Nyiva Mwendwa as the first female Minister and given her the portfolio of Culture and Social Services.

This situation was clearly untenable. I not only publicly declined the shadow position as Secretary for Culture and Social Services, but also resigned from my elected party position as Secretary for Legal and Constitutional Affairs, in order to give way to my party leader’s preferred appointee.

I was roundly criticised by party members who felt that my public rejection of the position was a form of insubordination of my party leader, a point of view I disagreed with. I turned my full attention to my responsibility as a DP Member of Parliament and an activist for social justice.

This was not the only controversial decision I had made in politics.

Much later in June 2001, President Moi visited my home district. It was a tradition then for Opposition Members of Parliament to boycott presidential functions due to hostilities between the Government and the Opposition. I decided to show up and welcome the President at Kerugoya Girls Secondary where his helicopter was due to land.

Buoyed by my presence, the President in his address to the schoolgirls, heaped praises on me, describing me as a good role model to them. After the welcome, I declined to accompany the presidential party to the district administrator’s residence where the President was being hosted for refreshments.

Instead, I opted to proceed directly to the Kerugoya Stadium, where the presidential function would be held. Being one of the early arrivals, I secured myself a good seat, and when the President arrived, I was just three seats away from him.

He at one point leaned over and asked me if I could join the ruling party Kanu, to which I replied by quoting his speech in 1963 when he was himself a member of the Opposition, Kadu: “Mr President, as you once said, without opposition there is no life. I will remain in the Opposition to put your government on its toes,” I said. He laughed off my response and let the matter rest.

As the speeches by local Kanu leaders got underway, the then-local Kanu Chairman for Kirinyaga, Mr James Njiru former MP for Ndia and a former Cabinet Minister in the Moi government was invited to speak.

He straight away embarked on berating the Opposition and its leadership, particularly my then-party chairman and leader of the Official Opposition Mr Mwai Kibaki.

I drew President Moi’s attention, asking him why he was allowing disparaging remarks against the Opposition and Mr Kibaki. President Moi made some vague remarks about not sharing the sentiments of Mr Njiru, his local party chairman, but did nothing to stop him.

I then asked President Moi if he could allow me to speak in defence of the Opposition. Again, he was vague, but his body language indicated his discomfort with my request.

I made up my mind there and then that I would walk out on President Moi as soon as he rose to speak. I scanned the immediate environment, aware that if I followed the President immediately, it would appear as though I wanted to attack him, and his security team would instinctively intervene.

I noticed another exit to the left of his podium a metre away and settled on it.

When President Moi was invited to speak, I paused for a minute or so to allow him to get to the podium before gathering my handbag and heading for the side exit. I then stopped in front of Moi’s podium and flashed the DP salute a clenched fist raised above my head.

I then walked towards the exit. I could hear President Moi clear his throat and then fall silent as I walked away, my clenched fist still raised. A few Kanu supporters had started jeering, but on realising that the President and his security detail were all watching silently, the hecklers too fell silent.

Amid the ensuing pin-drop silence, I marched to the exit of the stadium, with some of my supporters in tow. As I exited, the police swung into action, closing the gate as I entered my car to stop my supporters from leaving the stadium.

I drove slowly to Kerugoya town, accompanied by the people who had managed to leave the stadium before the gate was closed. I stopped at the Kirinyaga Tea Growers Sacco Building, now Bingwa Sacco within the town, where I used the raised staircase as a podium to address the now swelling crowd.

In less than 15 minutes, the presidential convoy left the town in a rush, an indication that the incident had jolted the President.

This incident earned the entire Opposition Moi’s attention. He proceeded to Meru after the incident, where he allowed Opposition Members of Parliament David Mwiraria and Kiraitu Murungi to address the people.

The following week, Moi was in Bungoma where, again, he gave the Opposition Members of Parliament a chance to speak. My walking out on him earned dividends for the Opposition.

I was now serving my second term in Parliament. Under the IPPG constitutional and legal amendments, Opposition parties could freely traverse the country marketing their ideas with ease.

We were, however, still dealing with a government keen on employing dirty tricks to obstruct the rule of law, subvert democracy and perpetuate the abuse of human rights.

During the IPPG reforms, the government committed to a comprehensive constitutional review after the 1997 General Election.

This process formally started with the bi-partisan enactment of the Constitution of Kenya Review Act of 1998. The Act provided for gender quotas on all the review organs. Under the umbrella of the Women’s Political Caucus, women were required to nominate five of the 15 commissioners.

As the chair of the League of Women voters, I was unanimously elected to chair the panel that would pick the five members, while Martha Koome, then-chair of Fida-Kenya, was elected as the secretary.

Other members were the late Jane Kiano, then patron of the Kanu Maendeleo ya Wanawake Organisation and Zipporah Kittony, who was the organisation’s chairperson.

Immediately after the selection of these women commissioners, a fissure occurred in the women’s movement. A group that was believed to enjoy the tacit support of the Executive went to court to stop the five nominees from assuming office, accusing the nominating panel of unfairness in the seletion of the commissioners.

Our legal team led by Ms Raychelle Omamo carried the day in court. The court dismissed the case, paving the way for the nominees to assume office.

We were aware that the Kanu administration did not want the review process to commence with the assertive women nominees as part of the review team. After many months of going around in circles, the process stalled and was eventually scuttled by disagreements over the nomination of the remaining 10 commissioners.

There was much drama in the national political arena. The National Democratic Party (NDP) led by Mr Odinga, then-Member of Parliament for Lang’ata Constituency in Nairobi, merged with the ruling party Kanu, weakening the Opposition ahead of the 2002 General Election.

With the warmth of this new Kanu-NDP alliance, the Government brought a Bill to Parliament seeking to amend the Constitution of Kenya Review Act to re-ignite the stalled constitutional review process.

This was done without any consultation, leading the Opposition to walk out of Parliament while the amendments were being debated.

Opposition leader, Mr Kibaki, and Mr Wamalwa Kijana leader of FORD Kenya the second largest Opposition party-led the walkout.

I decided not to walk out with the rest, remaining behind so that my objections to the proposed amendments could go on record. I needed to oppose the Bill on the floor of the House.

I explained this to my party leader, Mr Kibaki, and he understood. When the debate commenced, I gave reasons for opposing the Bill amidst a barrage of interruptions by the government side, whose members raised countless points of order.

I warned the government that even though they had the opportunity to bulldoze the amendments, Parliament would most probably have to revisit them in the fullness of time to make the process inclusive.

After my address, I, too, walked out of the House to join my Opposition colleagues, happy that my objections would remain on record for posterity. Members of the government side went ahead and passed the amendments.

The government, now keen to make progress with the constitutional review process, head hunted the renowned law scholar, Prof Yash Pal Ghai, then working abroad, to head the Constitution review process.

Prof Ghai accepted the Government’s appointment on condition that he would be given a free hand to unite the Government and Ufungamano parallel processes into one, which he successfully did.

Consequently, the Constitution of Kenya Review Act was once again brought to Parliament for amendment to facilitate an inclusive national pro- cess with bipartisan support.

Towards the end of 2001, the government side mooted the idea of extending President Moi’s term by a year, ostensibly to complete the review process. This proposal was tabled in the House Business Committee where Mr Kibaki, David Mwiraria, Norman Nyaga and I sat as representatives of the Democratic Party.

I opposed the proposal, and the matter was dropped from the agenda before it could be presented in the National Assembly for debate.

The proposal may have sounded reasonable except that we knew he was not a constitutional review enthusiast. The presence of Mr Odinga, who had been part of the constitution reform process, convinced most of the committee members, including my party leader Mr Kibaki, to support the idea. I was, however, not convinced and became the sole opponent of the proposal.

My objection did not sit well with the government. I had to endure accusations of arrogance by members of the government, who wondered how I could oppose a position my party leader was agreeable to.

I suspected that push for the extension was to enable President Moi to finish another year in order to celebrate his silver jubilee in office.

The press got wind of the attempt by Kanu to extend President Moi’s term by one year. This story sparked a national uproar, causing the government to beat a hasty retreat in the next committee meeting. The idea was completely abandoned.

A few months before the elections, the Government orchestrated the disbandment of the review process and stopped funding it, thus confirming my fears that President Moi and his administration never intended to have the review process concluded in the first place. We were back where we started.

The Opposition was determined to get things right in the runner-up to the 2002 General Election, having learned their lessons in the 1992 and 1997 elections that splitting the Opposition vote always gave the ruling party, Kanu, an upper hand.

The key opposition parties then-DP led by Mwai Kibaki, SDP, and FORD Kenya came together to form the National Alliance Party of Kenya (NAK), the United Front, which would lead them to capture the hitherto elusive leadership of the country.

The party leaders held regular strategy consultations which were informally referred to as “tea meetings”, as they sought to craft a winning formula and put together a formidable team.

After one such meeting, they were asked by journalists what they had discussed, and Mr Wamalwa and Ms Ngilu replied that they had met “for tea”. One journalist asked whether it was just about tea and no politics, to which Mr Kibaki cheekily quipped: “Tea can be very political”.

As the talks went on, the political marriage between NDP and Kanu was starting to become shaky. President Moi gave indications that his preferred successor was Mr Uhuru Kenyatta, then a political greenhorn, who had been nominated first to Parliament in 2001 and quick succession, to the Cabinet as Minister for Local Government.

Soon after the President made his decision public, Mr Odinga, who was one of the presidential hopefuls, led a mass walkout from Kanu to his recently acquired Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

One thing led to another and soon after, we all united under the umbrella of the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), whose symbol was the flame of peace. The closing of ranks by the Opposition was a game-changer, leading to rebirth of the Kenyan republic under Mr. Kibaki in 2002.

The book was published with support of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation Regional Office, South Africa. It’s available in leading bookshops.