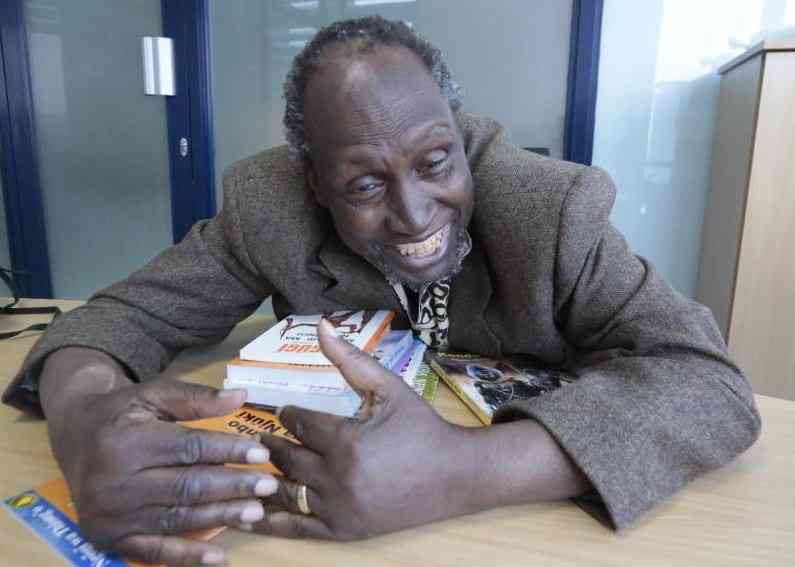

There’s a way that laughter easily fills up the spaces in our house in Gĩtogothi. It is early evening, and I am just about to have tea when my father, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, calls me. He is in the bedroom, his head on a pillow, leaning against the headboard. He is in brown corduroy pants, legs crossed at the ankles, his hands interlocked behind his head. My mother, Nyambura wa Ngũgĩ, in a flowing dress with yellow flowers interwoven between, is beside him perusing the dailies. They look like they are headed out on a date.

“Ndũcũ,” he starts, “there’s this cartoon in the papers that reminded me of you…show him,” he smiles.

My mother opens the pages and points to a cartoon character whose name escapes me. It is a boy, captioned whispering to his mother that they will eat the delicate food she had prepared after the guests leave. It is whispered, but it is loud enough for the guest to hear. As I read it, my parents are in jolts of laughter. At first, I don’t see the humor, but it’s the way they are rolling with laughter that makes me laugh. I try to defend myself against such a similarity, but truth be told, I have been known for such faux pas.

At Kanunga High School in the late 80’s I was ‘unfortunate’ enough to have Baba’s novel, The River Between, as a set book. Our literature teacher, Mrs G, had been my father’s student at the University of Nairobi some time back, a point she belabored into my ears. She was a good teacher, and I enjoyed how she showed us the depth and beauty of words, of writing, and the joy of reading.

In one class, after such an impassioned presentation, she asked how the River Honia functioned as a metaphor in connection to present-day political dynamics…” The class was deathly quiet. Mrs G was not a teacher to play with. We were all hoping that someone had been paying attention. As the teacher derided our lack of imagination, a friend of mine raised his hand. There was a collective sigh of relief.

“Yes, please tell us,” Mrs G thundered.

“Well, I just figured we are all struggling needlessly, and we could just ask Ndũcũ here to get us the answer from his father. After all….” He did not finish. Mrs G was livid. She sentenced the whole class to silence, a re-reading of preceding chapters, and to a two-page reflection on the question at hand, by the next day!

I had told this story to my father on several occasions, and each time it solicited guttural laughter. His shoulders rose and fell like the keys of a piano in the hands of a maestro. My sister Ngĩna, she of quiet humor, chimed in. “Yes, you should have told them you will seek the doctor’s advice…” She was playing with the word Honia.

After the laughter, there was a mini-lecture on the polemics of words, imagery, and symbolism, and how readers bring their lived experiences to the text-to a dance. That was my father-always a teacher.

A few weeks ago, I reminded him of a time when, in my quest to defy the laws of gravity, I convinced my brothers, Tee and Kĩmunya, to jump from the rooftop of our house in Tigoni at the time. I could hear his melodic laughter on the line.

Being with him was an experience in and of itself. He told stories easily. He cherished moments of levity, and in our family, we might as well be comedians. This laughter has sustained us through some tough times: his detention without trial, thugs breaking into our house and seriously injuring our mother, the silence of former friends, and the distance of exile.

My sisters Wanjikũ and Njoki have his laughter. I hear it when they crack up (sometimes at their own jokes). It’s light and comes from a place of depth and love. It comes the same way my father would break into song, making it up as he goes to his piano to accompany his terrible singing. We were often saved by his fingers, which were slow to find the right key and on time. But he was a persistent man. He started taking piano lessons in his early eighties! He enjoyed listening to his granddaughters, the Nyamburas, all of whom play multiple musical instruments and decided, I presume, to join what might be the family symphony orchestra.

One day, he called me and said, ” Listen here, young man.” I could hear him shuffling to the sitting room to get to the piano. “Can you hear me?” he asked. He cleared his voice, and I think, oh no! not the singing. But he played a tune. Slowly. Not half bad, I thought to myself. As he continued, his fingers got faster and more confident. And I recognized it. It was Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy.’ He had been practicing patiently and with relentless determination, the same commitment he has for promoting and delegating African Languages to the table of languages as co-equal transmitters of knowledge and culture.

“Ndũcũ reke ngwĩre ma, gũtirĩ rũthiomi thĩ ĩno rwĩ bata gũkĩra rũrĩa rũũngĩ!” I nod in agreement. He smiles, a shine in his eyes. “How far is the novel?” he asks. Between us, (Baba, Wanjīkũ, and Tee), we have an ongoing challenge: write a novel in Gĩkũyũ!

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

I tell him I will be writing night and day as soon as I get started. Well, he probes and I let it out that I have started mine– two paragraphs in. He wants to know more. But I am not about to give him “ideas.”

Instead, I tell him about Jack Chidi, the main character in my novel. There’s foreshadowing he likes: Chidi is walking up the stairs of the DCI office and runs out of breath. As he stops to collect himself, he mutters something about getting back to boxing as he used to back in the day. Later, he unleashes a rather generous beating on some bad guy. “Of course!” Baba thunders!

He lets out his signature guttural laughter, and I can see him replaying the scene.

“I can see you in him,” he finally says, “except you were a break-dancer in High school, right? And you danced in Nairobi? He asks incredulously.

“Yes,” I answer. I have told him this story, and each time I add details as I recall them, with some creative license.

“Did your mother know about this?” he chuckles at my mischief.

I tell him that she had come home once and told my brothers and sisters, “ I think I saw Ndũcũ in Nairobi…”

My father is laughing.

This is what I will miss. The cheerfulness, the easy conversations about life, and the lessons learned in this journey. It is the laughter that fills the spaces between home and exile, between the words on a page, and the laughter that embraces with its warmth.