The battle between Supreme Court judges and the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) boils down to four issues, including whether a judge can be punished for recusing themselves when a party raises claims of bias.

This comes as the Judiciary last week urged former Cabinet minister Raphael Tuju to stop litigating his wars with the East Africa Development Bank (EADB) in public as there are live cases.

The Judiciary Spokesperson, Paul Ndemo, said that following Tuju’s application to the Supreme Court to freeze the application of a UK judgement in favour of the bank, he filed a complaint before the JSC claiming bias.

According to Ndemo, this caused the Supreme Court to recuse itself. The net effect was that the judgement of the Court of Appeal, which also dismissed his case, remained in force.

Ndemo added that Tuju’s firm, Dari Ltd, filed yet another application before the High Court in September last year to stop the auctioning of his property, which was dismissed.

He asserted that Tuju is still in court over the property. In July, 2021, he filed a case before the East Africa Court of Justice, and he still has other cases before the High Court.

“It is, therefore, clear that the matters between Dari Ltd and EADB are actively before competent courts and the JSC. In accordance with the sub judice rule — which upholds the rule of law and the due administration of justice — these issues should be left for judicial determination and resolution by the JSC. We urge all parties to refrain from litigating their cases through the media or on social media platforms,” said Ndemo.

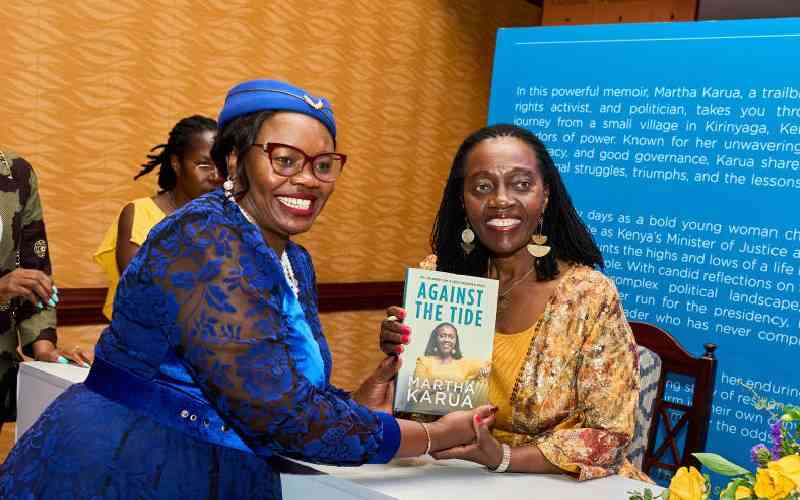

Tuju is among two petitioners seeking the removal of Chief Justice Martha Koome, her deputy Philomena Mwilu, and Justices Mohamed Ibrahim, Smokin Wanjala, Njoki Ndung’u, Isaac Lenaola and William Ouko.

The commission’s powers in processing the petition are central to their cases filed separately.

The seven senior judges argue that JSC cannot entertain petitions that amount to a review of their judgements or rulings.

In her case, the CJ argues that the petitions undermine the Judiciary’s independence. According to her, judicial independence has two main elements: decisional independence and institutional independence.

She is of the view that judges enjoy immunity for exercising their decisional independence.

“This has been encapsulated in Article 16 of the Constitution, which insulates members of the Judiciary from any action or suit in respect of anything done or omitted to be done in good faith in the lawful performance of a judicial function,” argues CJ lawyer George Oraro.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

On judicial independence, Mwilu argues that the petitions are hinged on decisions made by the court, which is an official judicial role.

Ibrahim, Wanjala, Njoki, Lenaola and Ouko hold a similar view that it is not open for the commission to interfere with the independence of the Judiciary.

The other issue before the court is whether the entire Supreme Court can be removed from office.

Mwilu argues that the Constitution does not contemplate a blanket petition. According to her, the law requires each judge to carry their own burden. Instead, she says, it is illegal to demand a judge should be removed from office based on a unanimous decision with his or her colleagues.

The DCJ says that the commission erred by requiring her to respond to the petitions filed by lawyer Nelson Havi knowing too well that it was in the public domain that he and Ahmednasir Abdullahi had repeatedly attacked the apex court on social media without providing proof of their allegations.

“The first and second interested parties petitions and or complaints are simply choreographed and targeted blanket war against the Supreme Court which at best is intended to have me and all the judges of the Supreme Court to be vetted afresh, even though we were each individually subjected to interviews and an audit to ascertain our suitability and competence to be appointed as judges of the Supreme Court,” says DCJ.

Ibrahim sees the petitions as personal grudges, targeted especially to the CJ. He argues that this can be seen in Havi’s writing about the CJ and the Supreme Court judges.

“The JSC petition is nothing but a sham or a disguised personal vendetta that the second interested party has against the judges of the Supreme Court in general, and the Chief Justice honourable lady Justice Martha Koome, in particular.”

Further, Lenaola argues that each judge is appointed individually and that any petition ought to be made against each judge individually rather than as a collective issue.

“The removal of a judge from office can only be justified where shortcomings complained of are of such a serious nature to destroy the confidence in the judge’s ability to properly perform his duty,” he says.

The other issue is whether parties ought to rush to the commission in a challenge of a court order.

Ouko says that the only options the Constitution offers are to move to a higher court or seek a review. According to the judge, the commission is not empowered to reconsider, review, set aside proceedings, give directions on how a case can proceed, or even issue judgements or rulings.

Njoki, on the other hand, argues that it is illegal for the commission to consider petitions when it is known that litigants are seeking multiple remedies for the same issue.

She says that the issues of Dari and Ahmednasir are actively before the High Court, making it subjudice for the commission to seek for answers from the judges.

In the meantime, Justice Ouko says the judges were also subjected to public scrutiny in an announcement by the commission’s deputy chair, Isaac Ruto, without verified claims.

“Its actions have given the impression that the Supreme Court and its judges are unworthy of public trust, creating a perception of wrongdoing where none has been established. Such actions by the JSC weakened the standing of the entire judiciary and the Supreme Court, in particular in the eyes of the public, and unduly threatened its institutional legitimacy,” he says.

The other issue is on whether JSC can punish a judge for recusing himself or herself in a case. According to the seven judges, the commission has no regulations to process the petitions, which leads it to pass any petition without passing the benchmark set by the law.

They assert that their decision to recuse themselves in the Dari case was because Tuju had written to the commission claiming bias on their end.

At the same time, they stated there is a separate case before the High Court where Tuju sued the apex court over the decision.