It is almost 10 years now since controversial businessman Jacob Juma was shot dead in cold blood on Ngong Road, Nairobi.

Juma, then a fearless government critic, was driving homefrom a bar to his residence in an upmarket estate when unknown gunmen sprayed his car with bullets before fleeing on a motorcycle.

The attack happened in an open area, under the glare of CCTV cameras and witnesses, circumstances that should have made it easy to trace his last moments and identify the killers.

Yet, a decade later, the masterminds remain unknown as the case went cold, a situation security experts say has become normalized in Kenya.

Typically, a killing occurs, authorities pledge which action, but soon the case fades, until another murder takes its place.

In July 2017, IEBC Information Technology manager Chris Musando was reported missing. A day later, his body was discovered in Muguga Forest, Kiambu County. The body of Maryanne Wairimu Ngumbu was also found just metres away.

Although several suspects were arrested in connection with Musando’s murder, the circumstances of the killing remain unclear. The case went cold after two suspects were released in 2020 for lack of evidence.

Like many other murders of Kenyans under mysterious circumstances, the case fell silent despite repeated police promises that no stone would be left unturned.

Security experts and human rights groups have since accused the police of failing to cooperate and withholding crucial information.

This comes in the wake of the killing of prominent lawyer Mathew Kyalo Mbobu, whose life was cut short on Tuesday along Magadi Road in Karen South. Witnesses said two assailants on a motorbike shot Mbobu at around 6pm.

The Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) said it is committed to ensuring the perpetrators are brought to justice.

Little information

However, International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) Executive Director Eric Mukoya noted that, apart from the killing of MP Ong’ondo Were in May this year, little information has been shared about past murders, especially those involving gun attacks.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

“It is difficult to get information from the police service in this country—even when you look at the principles of open governance,” Mukoya said. He added: “We have asked questions about investigations not only of people who have been shot, but also of those who have disappeared, those killed by police, and even police officers who have suffered in the line of duty.”

Mukoya said ICJ, which sits on several civil society security platforms, has consistently raised questions around murders. Yet, he noted, the process remains opaque—both in terms of investigations and in how the police service itself operates.

Recently, the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA) also complained about lack of cooperation from state agencies, a situation that continues to hinder its ability to fulfill its statutory mandate.

Lack of cooperation

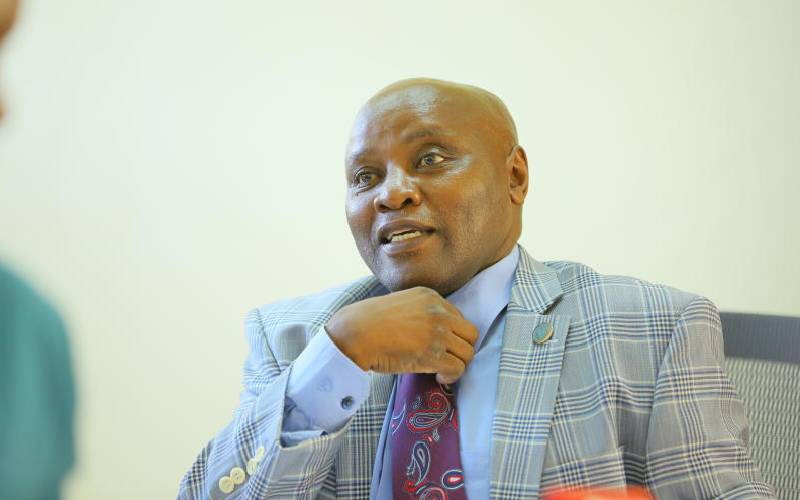

During a television interview, commissioner John Waiganjo said the agency has been unable to properly investigate some cases due to police failing to cooperate as required by law.

“We want the public to know we are working under very tough conditions. In IPOA’s lifetime, we have never witnessed the level of non-cooperation we are seeing now from senior police officers,” he said.

According to Waiganjo, police often control key files crucial to investigations, yet accessing such documentation is nearly impossible.

Several murder cases remain unresolved, among them that of Paul Ngugi, a land dealer shot 13 times along Forest Road in 2019.

Another is the killing of land broker Jared Aachok, who was gunned down in broad daylight on October 4, 2014, along Manyanja Road in Umoja Estate while heading to town. Assailants in a vehicle first blocked his car, shot at the driver, then turned on Aachok, who was seated in the back.

Vocal Africa, a human rights and social justice organisation, says it has also faced difficulties obtaining information from the police.

“I can say they are extremely uncooperative. They feel that when they share information, they are snitching on their colleagues,” said the organisation’s chief, Hussein Khalid.

He added: “In some recent cases, police have even refused to issue OB numbers, which simply confirm that a matter was reported. Without an OB, families cannot proceed with a postmortem in cases of death.”

Hussein recalled one case where a victim lived with a bullet lodged in his leg for a year because police denied him an OB number, preventing the hospital from removing it.

“The hospital needed the document so that once they removed the bullet, it could be handed over to the police. It only happened after we intervened, since the police insisted they hadn’t shot the victim,” Hussein said.