Refugees living in Kenya will not gain citizenship or voting rights under the government’s new Shirika Plan, which seeks to integrate them into host communities.

The Department of Refugee Services (DRS) says the integration plan will only provide socio-economic inclusion and pathways to self-reliance and not political or civil rights.

This comes amid a change in management of refugee affairs that will see a shift from the provision of humanitarian aid to socio-economic integration.

Khalif Ibrahim, a legal officer at the DRS, said the integration plan will cost Sh120 billion (approximately USD943 million) and will enable refugees to participate in economic activities.

“In other countries, integration allows refugees the right to gain citizenship and voting rights after maybe five years, but that is not the case for Kenya. The integration will only enable the refugees’ right to economic development and growth for self-reliance,” he said.

The official spoke during the Access to Labour Markets for Refugees East Africa Forum 2025, hosted by the Refugee Consortium of Kenya and the IKEA Foundation.

He added that the government is shifting from aid-dependent systems to integrated structures due to funding shortages and the need for sustainable solutions.

“The government is moving from a policy approach to a more integrated set of rules because funding is dwindling. We need sustainable solutions that allow refugees and host communities to be self-reliant,” he explained.

However, human rights experts say refugees continue to face severe barriers in accessing their rights, particularly employment, documentation, and labour mobility.

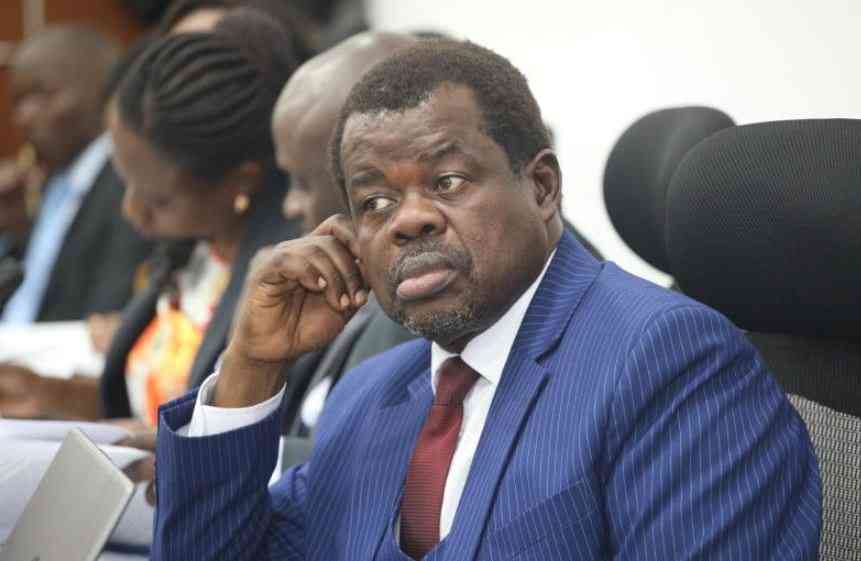

Osman Abdikadir of the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) said despite progressive laws, the weak enforcement and deeply entrenched bureaucratic hurdles have barred progress.

He explained that refugees seeking work permits must navigate multiple layers of administrative barriers, including complex and technical application forms, mandatory letters from DRS and employers and long approval delays.

Kenya hosts about 870,000 refugees. Dadaab leads with over 560,000, Kakuma–Kalobeyei complex hosts close to 400,000, while more than 117,000 live in major urban centres including Nairobi, Mombasa and Eldoret.

The integration known as Shirika Plan will be done over 15 years in three phases, with the first being the transition running between 2025 and 2028. The phase, currently in implementation, focuses on legal reforms, including amendments to 18 laws.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

The second phase will be the stabilisation phase (2029–2032) to align institutions and reduce policy bottlenecks, and the final phase is the resilience phase, where refugees are expected to achieve full socio-economic participation after barriers are removed.

The government acknowledges that both refugees and host communities have shown resistance to the plan. “Refugees have not been welcoming, and host communities have also not been welcoming,” Ibrahim said, adding that extensive sensitisation will be required.

Movement also remains restricted, with refugees required to obtain a movement pass.

Officials attending the forum have proposed a gradual relaxation, beginning with movement within municipalities and later counties.

DRS also revealed that a digital refugee database is being developed to reduce bureaucracies such as the need for DRS letters when accessing services including health, work permits and housing.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has welcomed the move, saying it will improve livelihoods and reduce administrative barriers.

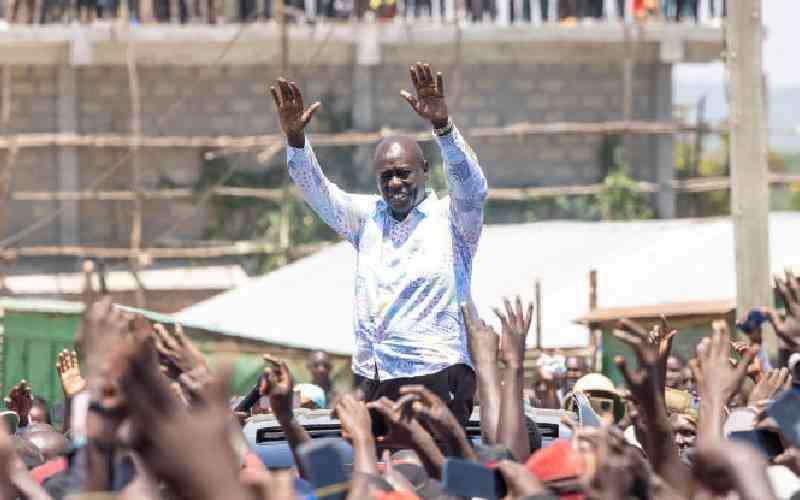

Andrew Agumba, UNHCR’s Livelihoods and Social Protection Lead, said refugees can contribute significantly to local economies when legal and operational barriers are removed.

Agumba further stated that high unemployment rates across the region severely constrain labour mobility, and until labour markets expand, both refugees and nationals will continue to struggle.

He has called for a deeper involvement of the private sector to create more job opportunities. “The market itself is too small. You cannot build a market for refugees without building a market for the region,” Agumba said.

At the same time, Ibrahim noted that as part of the reforms, Kenya is exploring how to fund refugee learners once schools in camps are fully integrated into the public system.

Currently, capitation is only provided for Kenyan nationals, leaving a gap in financing that must be addressed as refugee schools transition into government-led institutions.

“When schools in the camps are registered as public, we must decide who caters for capitation for refugee students,” Ibrahim noted.

Similarly, the DRS has revealed plans to work with the Teachers Service Commission(TSC) to review the laws governing the teachers’ employer and regulate teaching in refugee schools.

Accordin to Ibrahim, most teachers currently serving in refugee schools are not TSC-certified, a gap the government intends to close to standardise education delivery in the camps.