The Ministry of Lands has long been a hub of controversy in the country with land fraud cases piling up and innocent citizens losing their property rights.

A recent ruling by the Court of Appeal has revealed the extent to which unscrupulous cartels have infiltrated the Ministry, particularly at its Nairobi headquarters, Arthi House, and exposed a deeply embedded culture of corruption.

The Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning, housed at Arthi House in Nairobi, is meant to be a public service institution overseeing the fair and transparent management of land in Kenya.

However, for years, it has been shrouded in scandal, with multiple reports of land fraud, illegal transactions, and the manipulation of land records.

The term “Arthi House Cartels” has become synonymous with corruption, as investigations and whistleblower testimonies have pointed to the existence of a well-organized network of officials facilitating fraudulent land deals.

These cartels, consisting of corrupt officers and middlemen have allegedly been altering land titles, forging signatures, issuing fraudulent title deeds, and even disappearing critical land records to pave the way for illegal acquisitions.

The consequences of these actions have been devastating: genuine landowners have been dispossessed of their property, and innocent people have found themselves embroiled in lengthy, costly forced court battles that can take years to resolve while their rightful properties are stolen out from under them.

In a landmark judgement, the Court of Appeal exposed these illicit practices and called for accountability within the Ministry of Lands, particularly Arthi House.

The Court of Appeal President David Musinga, alongside Justices Kathurima M’Inoti and Fred Ochieng in a unanimous decision took the rare step of publicly highlighting the role of rogue officers within land registries who enable the alteration of land documents, illegal issuance of land titles, and the disappearance of vital land records.

These corrupt practices, according to the judges, have significantly not only undermined the security of land ownership but also prolonged the growing backlog of land-related cases, which clog the judicial system.

“Fraudulent land dealings in this country, often facilitated by a few unscrupulous officers at various land registries, who facilitate unlawful alteration of land documents; issuance of fake or unauthorized documents, or cause ‘loss’ of vital land records, among other malfeasances, have substantially contributed to long drawn-out cases in our courts,” the Musinga led bench stated.

In their judgment, they condemned the corrupt activities that have become the hallmark of land transactions in the country for years and demanding a much-needed reform of the system to restore justice and integrity to the country’s land management processes.

The judges further emphasized that land ownership and land rights are both historically and emotionally charged issues in Kenya.

“A right to hold property is a constitutional right, as well as a woman’s right, and no person should be deprived of their property except in accordance with the provisions of the constitution or statute,” the judges affirmed.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

The ruling stemmed from a long-running land dispute involving Mas Construction Limited, which had filed an appeal against a decision made by the Environment and Land Court.

The case was marked by a series of fraudulent actions, including wrongful eviction, fabricated debts, and corrupt land dealings, such as the issuance of two titles for the same parcel of land by the Land Ministry and disappearance of the original title.

At the center of this dispute were Abdul Waheed Sheikh and Abdul Hameed Sheikh, two brothers who had been in possession of the disputed property, located along 1st Parklands Avenue in Nairobi, for decades.

The land, which had been registered in the name of their late father, Sheikh Fazal Ilahi, had been in the family since 1937.

The Abduls were fighting not just for their property but also to protect their family’s legacy.

The dispute began when Mas Construction claimed that the Abduls’ tenants were in arrears of rent, a claim that was later revealed to be completely false.

On October 10, 2014, Mas construction employed an auctioneer, Joseph Nderitu t/a Jogandries Auctioneers who broke into a residence on the disputed land and went to great lengths to forcefully evict the occupants, including demolishing the property.

The company then used fabricated debt of Sh 700,000 as the basis for a wrongful eviction of the occupants, including Abduls’ caretaker and her husband, Ngina Kimeu and Jackson Muema.

According to evidence adduced in court, the company also used a Chief Magistrates Court order obtained from Milimani Law Courts to unlawfully seize their property, including personal belongings.

This action was a clear violation of the Abduls’ rights to hold and enjoy their property.

In response to the unlawful eviction, the Abduls lodged a lawsuit at the Environment and Lands court seeking to nullify the court order that had permitted the eviction.

They argued that the tenants were not Mas Construction’s tenants and that the eviction was a deliberate attempt to dispossess them of their inheritance through fraudulent means.

Their claims were supported by historical documents, including land rate and rent payment records, which demonstrated their continued ownership of the property.

Mas Construction, however, argued that it had legally purchased the land from businessmn, Hassan Abdi Salan and Mahat Adan Abdirahman Ibrahim, who had no connection to the Abduls.

The firm through Chueb Adan Ali, its director testified that Mas construction purchased LR No. 209/1916/5 from Salan and Ibrahim for sum of Sh 25 million.

He claimed that he conducted thorough due diligence before the purchase and found the property registered in the names of the Salan and Ibrahim.

Cheub claimed that the company paid land rates, obtained consent for the transfer, and proceeded with the registration process.

The company director informed the court that intended to develop apartments on the land and had obtained necessary approvals from Nairobi City County.

Chueb denied the Abduls’ claims, stating that his company’s title was valid and confirmed by the Chief Land Registrar.

He also denied any involvement in altering land records at the Lands registry.

The company’s defense also was built on the testimony of the Chief Land Registrar, who disowned the Abduls’ title deed and claimed that the property had never been registered in their father’s name.

According to the Chief Land Registrar, the property had never been transferred before April 1, 2003, and the Abduls’ documents were forgeries.

“I wish to state that, based on the available records, the appellant (Mas Construction) was the registered proprietor of the property, and that the Abduls or their deceased father’s estate had no claim over it whatsoever,” the Chief Land Registrar told the court.

The Abduls countered these claims, asserting that they had paid land rates for the property for decades, and that the title they held was legitimate.

They argued that Mas Construction’s actions to alter the land records were rooted in fraud in attempt to support its false claims of ownership.

Abdul Hameed Sheikh, one of the Abduls, further clarified the history of the property.

He testified that LR No. 209/1916/5 had been transferred to their father, Sheikh Fazal Ilahi, in 1937 and was registered in his name.

After their father’s death in 1955, Abdul Ghafoor Sheikh obtained a limited grant of probate, and later, Abdul Shakoor Sheikh obtained the grant of letters of administration for the estate.

Abdul Hameed testified that after Abdul Shakoor’s death in 2010, the Abduls acquired a grant of letters of administration.

He maintained that the Abduls were the rightful owners of the property, as they had maintained continuous possession for over 70 years.

David Gacanja Kago, a licensed land surveyor, testified in court, providing a clear historical overview of the property.

He explained that the land had been subdivided multiple times, and the property in question was originally under leasehold for 99 years from April 1, 1904.

Kago’s investigation revealed that the Abduls had applied for and successfully extended the lease in 2003, further solidifying their claim to the property.

“A grant in favor of the Abduls was issued in 2003, while the grant to the alleged initial owners, Salan and Ibrahim, was issued on February 18, 2013,” Kago explained

Kago also presented a Deed Plan in court, which had been lawfully procured by the Abduls.

He also revealed that the Deed Plan revealed that Salan had submitted an affidavit to the Director of Surveys, stating that he had lost the original Deed Plan.

The Abduls’ legal battle revealed disturbing evidence of corruption at the Ministry of Lands.

Ms. Gildine Gatwiri Karani, the Principal Land Registration Officer, testified that the deed file for the Abduls’ title had gone missing in 2013.

She confirmed that Mas construction title was linked to the creation of a new deed file (IR 147524) in 2013, but expressed concerns about the unprocedural nature of registering two different titles for the same land.

Karani highlighted discrepancies in the issuance of these titles, particularly regarding the process and the procedure under which grant IR 147524 came into being led to the creation of two conflicting titles for the same property.

After years of legal wrangling, Justice Oscar Angote of the Environment and Land Court ruled in favor of the Abduls, declaring the court order of October 10, 2014 that had permitted the wrongful eviction null and void.

The court further ruled that the Grant Number IR 147524, claimed by Mas Construction, was invalid as the company’s title to the land was fraudulently acquired.

The judge concluded that while the company claimed to have lost the original deed plan, it had obtained a certified true copy to secure a parallel grant.

The court also confirmed that the land reference number 209/1916/5 was still rightfully owned by the Abduls, based on the historical evidence provided, which included payment records and the legitimate documents tied to their late father’s estate.

The court also addressed the issue of trespass stating that the Mas Construction along with the alleged owners Salan and Ibrahim had unlawfully entered the property and demolished a house.

The Abduls were awarded Sh10,000,000 in damages for trespass.

Mas Construction, unsatisfied with the decision, appealed the ruling before the Court of Appeal.

The company argued that the case could not be resolved without first investigating the origins of both the Abduls’ and Mas Construction’s titles.

They contended that their title was legitimate, backed by a letter of allotment dated March 3, 1997, and that the land had been properly registered in their favor in 2015.

However, the Court of Appeal dismissed Mas Construction’s appeal, reaffirming the lower court’s ruling.

In their Judgement, Justices Musinga, M’Inoti, and Ochieng found that the claim made by businessmen Salan and auctioneer Nderitu who contended that the land in question was unalienated government land before its allotment to them was without merit.

The judges firmly rejected the claim, stating: “That cannot be true. The original property had long been alienated, a leasehold interest having been issued for a term of 99 years from October 1, 1904, to April 1, 2003.

“The suit property was not therefore available for alienation. The Commissioner of Lands or any other office had no power to do so as it was not unalienated government land.”

The Court also found that businessman Salan had sworn a false affidavit to procure a certified copy of the Deed Plan from the Director of Surveys.

The judges explained, “He knew that he had never been in possession of that Deed Plan, and so by falsely swearing that he had misplaced it, when all along it was lawfully in the hands of the Abduls, Salan obtained the Deed Plan fraudulently. Salan and Ibraihim did not have a good title that they could pass on to Mas Constructions.”

The Court further agreed with the trial court’s findings, which held that Mas Construction’s title was “procured through fraud perpetuated through two ways: firstly, by obtaining a certified true copy of the Deed Plan, which the Abdul’s held, and secondly, procuring the opening of a Deed File IR 147524 on August 21, 2013, for a piece of land whose title was already in existence.”

The judges emphasized that this fraudulent scheme involved obtaining title to land that was already lawfully owned by another party, leading to the eventual nullification of the company’s claim.

The Court also ruled on the illegal demolition of a house standing on the suit property, which had been occupied by a caretaker of the Abduls.

The judges found that Mas Constructions, together with Salan and Ibraihim, had orchestrated a fraudulent exercise.

The Court noted that Mas Constructions admitted that it had not placed any tenant in the house, yet it instructed auctioneer Joseph Nderitu (trading as Jogandries Auctioneers) to levy distress for rent against the occupier, claiming unpaid rent of Sh 700,000.

The Court was unequivocal in its findings, stating: “The appellant and/or the appointed auctioneer went even further to demolish the house. We have no reason to disturb the award of Sh 10,000,000 that was made by the trial court.”

The judges characterized the acts of Mas Constructions, Salan, Ibrahim and auctioneer Nderitu as a “well-orchestrated, nefarious act” aimed at unlawfully acquiring the property and obtaining vacant possession to pave the way for the construction of apartments.

“Their well calculated moves must have been supported by some deceitful officers at the Lands Registry, Nairobi, who caused the Deed File for IR 94707 to go missing.

The heart of the dispute lay not just in who owned the land but in how fraudulent land dealings had been allowed to persist.

These dealings were facilitated by unscrupulous officers within the land registries, who were complicit in altering property documents, issuing fake titles, and “losing” key records.

This corruption allowed malicious parties to falsely claim ownership of land, causing untold suffering to rightful owners.

The system, meant to protect land rights, had become an instrument of dispossession, as Mas Construction’s claim was built on altered and fraudulent documents.

The Abduls’ legal battle, while rooted in personal loss, exposed a far larger issue that plagued the country’s land system: fraud and the exploitation of loopholes in a deeply flawed legal framework.

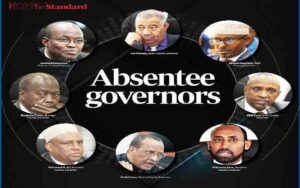

The case highlighted by the Court of Appeal is just one of many in which corrupt officers at the Ministry of Lands have facilitated fraudulent transactions.

Thousands of Kenyans across the country have faced similar challenges, where they have been defrauded of their legitimate land by serious racketeers, operating both within the land registries and beyond.

In Nairobi, the most places that have been hardest hit are like Lavington, Embakasi, Thome, Donholm and Eastleigh areas.

These racketeers have have led to instigation of numerous court cases in the Judiciary.

A review of some other cases pending or have been determined before the Court reveals a troubling trend.

Rightful landowners are being defrauded through tactics such as fabricating ownership documents, selling the same land multiple times, concealing existing liens or debts, and misrepresenting property information or location.

These actions often target unsuspecting buyers with false promises and irresistible deals.

Once the racketeers identify a piece of land they wish to “sell,” they alert their contacts at the Lands Ministry, who prepare parallel sets of fake documents to deceive the victims.

Martin Kivuva, one of the victims of the Syokimau demolitions in 2020 that saw him and others lose millions in investments, describes how he fell prey to these murky deals.

According to Kivuva, the racketeers are so meticulous that only a keen eye can detect the fraud.

“They are thorough, callous, and well-connected. They have conned several people out of their money, land, or houses,” he says.

Kivuva adds, “It’s almost unbelievable, but it works. I personally bought one such plot, lost my money, and later saw the property demolished.”

He explains that the documents for the land appeared to be original, and a search conducted at the land registry confirmed that everything seemed genuine.

“Where owner signatures are needed, they are forged. Because they retain original records, Lands offices attract the highest premiums. Original records are removed and destroyed. Once that’s done, the properties are conveniently sold and transferred. And the cartel moves on,” he says.

In another instance, is when the court allowed the eviction of settlers residing on the 1,000-acre land in Njiru, Nairobi, owned by the family of the late politician Gerishon Kirima.

In October 2023, Justice Samson Okong’o ordered the thousands of settlers to vacate the land after the court ruled that the Kirima family was the rightful owner.

“The plaintiff (Kirima family) has proved that the defendants did not obtain his consent before entering into his said parcels of land,” the judge ruled.

The settlers, who had resided on the disputed land for over a decade, faced eviction despite their claims that they had leaving on the land for over 40 to 50 years.

According to the cases filed in court challenging the eviction order, some claim that had been told by some individuals that they were the alleged legitimate owners of the land prompting them to buy and invest, own houses and rental flats and other businesses worth millions of shillings.

The former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua also fell victim to the alleged land fraud scheme at Ministry of Lands

His Sh1.5 billion land in Embakasi, Nairobi, was allegedly fraudulently taken by Michael Ohas Otieno, a former official at the Ministry of Lands.

In a suit determined in early 2024, Gachagua accused Ohas, a former director of physical planning at the Ministry and managing director of Columbus Two Thousand Ltd, of illegally and fraudulently obtaining a second title deed for the property, even though his own title still existed.

The former Deputy President accused Ohas of tampering with records at the land office.

According to Gachagua, the property was charged to Equity Bank as collateral for various financial facilities amounting to Sh200 million.

In court papers, Gachagua, through his company Wamunyoro Investments Ltd, stated that he was issued with the title for the property on June 18, 2012.

However, another title deed was later processed and issued to Columbus Two Thousand Ltd.

A judgment by Justice Joseph Mboya of the Milimani Environment and Land Court found Gachagua to be the legitimate owner of the multi-billion-shilling property.

The judge ruled that Gachagua’s company, Wamunyoro Investments Ltd, was the lawful owner of the two acres of land near Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Embakasi, Nairobi County

The judge further revoked the title deed issued to Ohas, a retired director at the Ministry, ruling that it had been fraudulently obtained.

“The second defendant’s (Ohas’s company, Columbus Two Thousand Limited) title was irregularly and illegally obtained and is therefore invalid and null and void,” the judge ordered.

At the heart of these illicit activities are cartels that operate with impunity, exploiting the Ministry’s outdated systems, lack of oversight, and the complex bureaucracy involved in land registration.

At Arthi House, the corruption appears to be almost institutionalized. Sources within the Ministry, speaking on condition of anonymity, have revealed that bribery and kickbacks are common practices among officials responsible for land registration and title issuance.

“It is an open secret that if you want your land transaction to go smoothly, you pay the right people,” the official disclosed, citing the sensitivity of the matter.

“Even the loss of records is often ‘arranged’ when needed for fraudulent deals.”

This has led to numerous cases of landowners losing their properties to individuals or companies who have bribed officials to falsify titles.

Kenya’s land disputes, many of which stem from fraudulent dealings, have created an environment of uncertainty and instability.

The result is widespread landlessness and displacement, particularly in rural areas where communities rely on land for survival.

key factors on the land cartels storY

- Corruption at the Ministry of Lands: The Ministry of Lands, especially at Arthi House in Nairobi, is heavily involved in land fraud cases due to widespread corruption by officials enabling fraudulent land transactions.

- Complicit Officials and Cartels: A network of corrupt officials and middlemen known as the “Arthi House Cartels” facilitates the alteration of land titles, issuance of fake title deeds, and manipulation of land records to acquire properties illegally. These cartels operate both within and outside the land registry system, collaborating in a well-organized scheme to exploit loopholes and deceive rightful landowners.

- The Abduls’ Family History and Ownership: The Abduls, whose family has owned the disputed land since 1937, have been fighting to retain their rightful property, which was registered in their deceased father’s name Sheikh Fazal Ilahi. They have consistently paid land rates and maintained possession of the property, which is located in Parklands in Nairobi, for over 70 years.

- Wrongful Eviction of the Abduls: The Abduls were wrongfully evicted from their property in October 2014, facilitated by Mas Construction through its director Chueb Adan Ali and the hired auctioneer, Joseph Nderitu. Mas Construction falsely claimed unpaid rent of Sh700,000. The eviction included the destruction of property and seizure of personal belongings.

- Fraudulent Title Deeds: Mas Construction claimed ownership of the land based on forged documents and a fraudulent title. They argued that they had purchased the land from two individuals, Hassan Abdi Salan and Mahat Adan Abdirahman Ibrahim, at a cost of Sh 25 million, who the court found had no legitimate claim to it

- Court of Appeal’s Role in Exposing Corruption: The Court of Appeal judges David Musinga, Kathurima M’Inoti, and Fred Ochieng condemned the fraudulent practices at the Ministry of Lands, emphasized the need for reforms, and reaffirmed the Abduls’ family ownership, stating that the title held by Mas Construction was fraudulently obtained.

- Disappearance of Vital Land Records: The land registry records were lost, altered, or forged, leading to the issuance of fraudulent title deeds and prolonged legal battles. Key officials at the Ministry of Lands were involved in these illicit activities, enabling the fraudulent claim of ownership by Mas Construction.

- Evidence of Forgery and Fraud: The case revealed how fraudulent documents, such as forged deed plans and fake title deeds, were used to support Mas Construction’s claims to the property, and how officials at the Ministry of Lands were complicit in these illegal actions. Two title deeds had been issued in respect to the land.

- Legal Struggles and Financial Toll: The Abduls endured a lengthy and expensive legal battle to reclaim their property for over 10 years, exposing the inefficiency of the land dispute resolution system and the emotional toll of being dispossessed of one’s land.