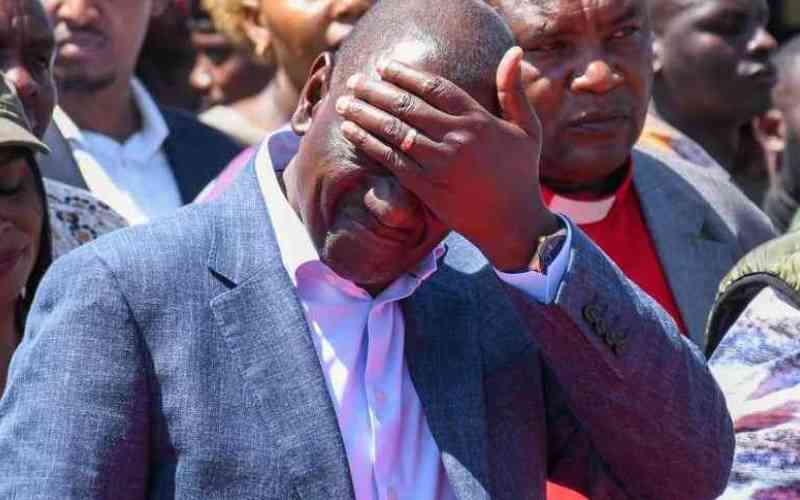

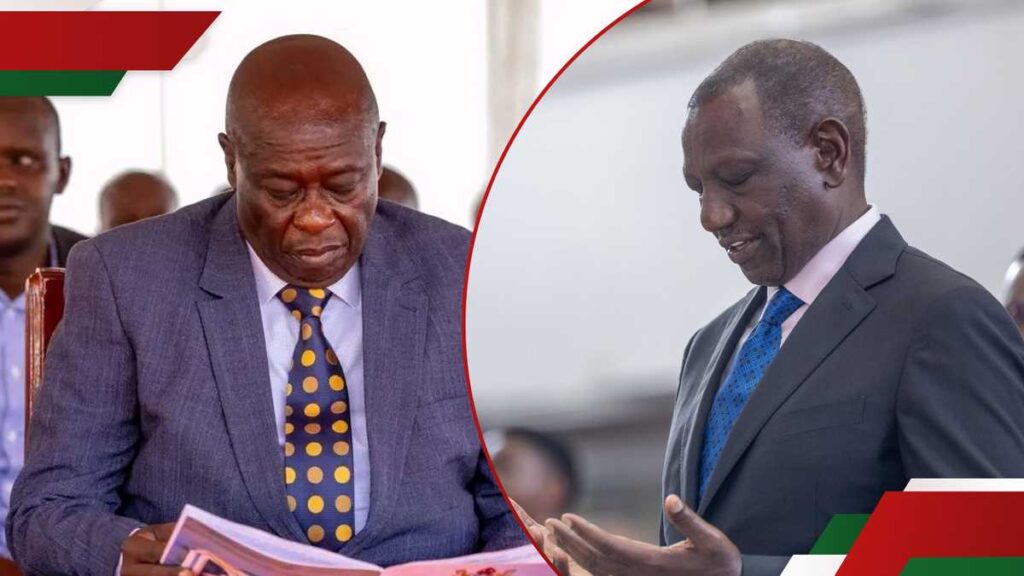

When President William Ruto issued a condolence message following the death of Kasipul MP Charles Ong’ondo Were, the reaction on social media was not one of grief. Instead, it was met with sarcasm, scorn, and, in some cases, celebration.

“If we continue at this rate—at least one MP per month—by 2027, Kenya will be free from corruption,” wrote James Ndugu on Facebook, a post that garnered hundreds of likes and shares.

It was not an isolated opinion. Dozens of Kenyans joined in, echoing the sentiment that the political elite had long ceased to represent the people.

The backlash, coming just weeks after Kenyans’ cold response to the death of Dagoretti North MP Beatrice Elachi’s son, reflects a growing chasm between the public and leaders.

In his condolence message, President Ruto instructed the police to conduct a thorough investigation into the MP’s death.

“Those responsible must be held accountable,” he said. But to many, the words rang hollow.

In life, Ong’ondo was mired in controversy, facing more than 20 allegations, including violence and intimidation. His death may have shocked Parliament, but not the public.

“Leadership demands truth—even when it’s uncomfortable,” said political analyst Martin Mureithi. “We should ask ourselves: how did such a man even get elected? What does that say about our politics?”

That disillusionment has been brewing for years but reached a boiling point in June 2024, when Parliament passed the controversial Finance Bill, triggering historic protests and an unprecedented breach of the House by angry demonstrators.

Even after the protests, President Ruto’s administration appeared more focused on damage control than reform.

Arnold Maliba, leader of the Progress Plus Alliance (PPA) party, said that on 25th June 2024, Kenya changed forever. According to him, it was a watershed moment, and only politicians remain hungover from the past.

“A majority of politicians think the country can return to pre-2024 Kenya. It’s not happening. They must accept that they serve at the pleasure of the voters, and that the mheshimiwa title is no passport to special treatment,” said Maliba.

A critical mass of citizens now demands leaders who reflect the spirit of the Constitution. Any attempts to revert to a Kanu-era type of politician are being firmly rejected.

Although President Ruto declined to sign the Finance Bill, the move was largely seen as a political strategy rather than a sincere response to public outcry.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

“The Bill passed with 195 votes for and 106 against, despite clear and loud opposition,” Maliba noted.

“It was yet another reminder that Parliament is no longer the people’s House—it has become a branch office of State House.”

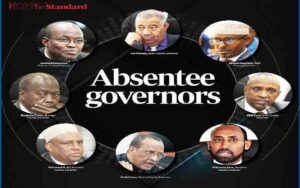

According to the Mzalendo Trust’s 2024 Parliamentary Scorecard, 19 MPs including high-profile ones such as Kapseret’s Oscar Sudi and Makadara’s George Aladwa, did not utter a single word in Parliament over the past year. UDA, President Ruto’s party, accounted for 10 of these silent MPs, while ODM had four.

Meanwhile, Parliament adjourned 66 times due to lack of quorum, 40 of those in the National Assembly.

“It’s not just that they’re not speaking, they’re not even showing up,” said Mzalendo researcher Janet Ogutu.

The report also revealed that public participation in legislation is increasingly treated as a mere formality. Bills with far-reaching consequences—such as the Basic Education Bill and the Affordable Housing Bill—were rushed through with only a few days allocated for public input.

“In a democracy, that’s unacceptable,” Ogutu said.

During election campaigns, Kenyan politicians promise roads, jobs, water, and dignity. But once in office, many pivot towards personal enrichment and loyalty to the President and party leaders.

“There’s a full-blown civil war between the people and their leaders. Citizens feel ignored, and leaders, driven by self-interest and entitlement, feel above accountability. The outcome is what we see,” Maliba warned.

Allegations that MPs were bribed with Sh2 million each to support the 2024 Finance Bill only added fuel to public anger. Juja MP George Koimburi claimed the payments were made in cash. National Assembly Speaker Moses Wetang’ula dismissed the allegations as dangerous and baseless—but the damage was already done.

Meanwhile, media reports suggest that MPs take as little as Sh10,000 to endorse reports or vote for bills.

“Kenyan politicians have perfected the art of ‘carrying their own weather’ and refusing to ‘read the room.’ We’ve now reached a point where it’s the ‘room’ that is reading them,” Maliba said.

Mandera North MP Bashir Abdullahi’s recent comments about the killing of demonstrators during last year’s protests sparked outrage.

“In a democratic country, it’s normal for people to get killed. We mourn and move on,” he said in Parliament, a statement many saw as cruel and indifferent.

Social media user Jecinter Wanjiru turned those words against him in the wake of Ong’ondo’s death: “Today, I agree with him… It’s normal in a democracy for an MP to be shot. We mourn and move on.”

Onyango Jagirango, son of a former MP who served during the Jomo Kenyatta and Moi eras, offered a sobering reflection.

“If my father were alive today, he wouldn’t qualify to serve. It now seems that to be an MP, one must be corrupt, violent, capable of murder, and skilled at lying,” he posted on Facebook.

He wasn’t speaking metaphorically. He said the late Ong’ondo had long faced allegations of abusive behaviour and intimidation.

“The people of Kasipul have been pleading for justice for years. He and those he hurt deserved their day in court,” Jagirango said. “If we continue down this path, who will be next?”

In the wake of the Finance Bill protests, activists called for urgent electoral reforms, including the reconstitution of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) and mechanisms to ease the recall of underperforming MPs.

“From the way things are going, the next Parliament will likely be filled with entirely new faces. In 2027, we’re looking at a complete overhaul of MPs and MCAs, because legislators have repeatedly pandered to executive interests and ignored the public,” Maliba said.

“It’s like we’re voting for ghosts,” said university student and protester Linet Mwikali. “They come to our towns, beg for votes, then vanish into Nairobi and forget us.”

To many young people, Parliament’s behaviour is symbolic of all that is wrong with governance in Kenya: empty chambers, ignored petitions, fast-tracked bills, and unchecked obedience to the Executive.

“We are not represented—we are ruled. Politicians want to dictate how we live, yet it’s the people who should determine how leaders lead,” said boda boda rider Daima Kimani, who was arrested during last year’s protests. “The only way out is to rise up and demand our country back.”

Nairobi businessman Fred Musau believes there is an urgent need to disarm and detoxify Kenya’s politics.

Musau added that many capable individuals have shied away from politics due to its violent nature.

“We’ve normalised violence and greed in our political culture. Here in Nairobi, no elected leader moves without at least five goons,” he said.

“I have no doubt this MP (Ong’ondo) was killed by a rival political gang—or something of the sort,” he added.

Civil society groups are demanding constitutional reforms to empower voters to recall ineffective MPs. Others are pushing for term limits, campaign spending caps, and independent vetting of candidates.

“We need a new social contract,” said Maliba. “One where power actually flows from the people, not from State House, not from party bosses, but from the grassroots.”

Human rights activist Boniface Akach, based in Kisumu, said MPs are part of a criminal syndicate, arguing that security agencies have shielded rogue politicians from justice.

“We’ve lost too many lives to intolerance. To survive in politics today, you need a gang,” he says.