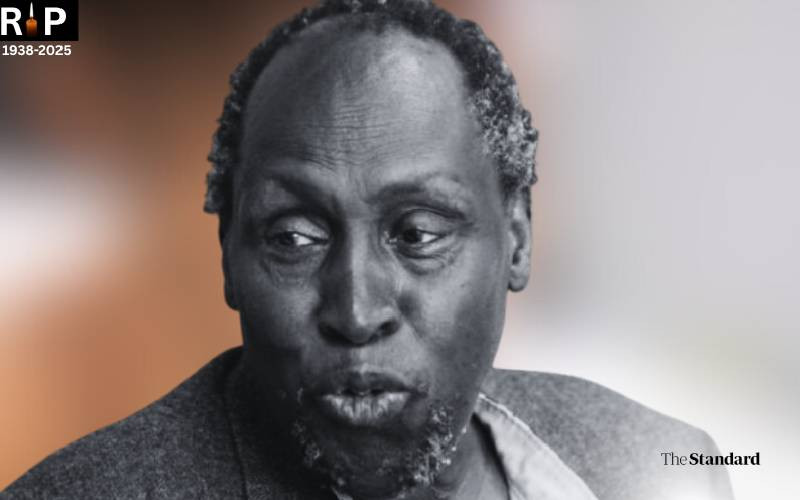

Renowned Kenyan author, academic and literary icon Prof Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who died on Wednesday, was more than a writer—he was a revolutionary thinker who used language, storytelling, and theatre as tools of liberation.

In his groundbreaking book Decolonising the Mind, Ngũgĩ championed the us of mother tongue, arguing that language was inseparable from culture, identity, and resistance. “To speak one’s language is to celebrate one’s identity,” he famously wrote, “but to impose a language is a way to divide people—it is to practice tribalism of another kind.”

Ngũgĩ believed that true empowerment lay in reclaiming one’s mother tongue. “If you know all the languages of the world but not your mother tongue, that is self-enslavement,” he wrote. “Knowing your mother tongue and all other languages too is empowerment.” To him, language was not just a communication tool, but the “collective memory bank of a people’s experience in history.”

When asked whether Kenyan English or Nigerian English were now local languages in 2013, the former freedom fighter said, “It’s like the enslaved being happy that theirs is a local version of enslavement. English is not an African language. French is not. Spanish is not. Kenyan or Nigerian English is nonsense. That’s an example of normalised abnormality. The colonised trying to claim the coloniser’s language is a sign of the success of enslavement.”

A voice to the exploited

His writings were often a defiant response to colonial and post-colonial oppression. He used storytelling to challenge systems of oppression and give voice to the marginalized. In Wizard of the Crow, for instance, Ngũgĩ illustrated how multiple layers of discrimination—racial, gendered, and economic—intersected to oppress the most vulnerable.

“I believe that black has been oppressed by white; female by male; peasant by landlord; and worker by lord of capital…. The black female worker and peasant is the most oppressed,” he wrote, “She is oppressed on account of her color like all black people in the world; she is oppressed on account of her gender like all women in the world; and she is exploited and oppressed on account of her class like all workers and peasants in the world. Three burdens she has to carry.”

In Devil on the Cross (1980), Ngũgĩ eloquently captured the existential struggle for dignity: “Our lives are a battlefield on which is fought a continuous war between the forces that are pledged to confirm our humanity and those determined to dismantle it; those who strive to build a protective wall around it, and those who wish to pull it down; those who seek to mold it, and those committed to breaking it up; those whose aim is to open our eyes, to make us see the light and look to tomorrow…”

On resistance and power of unity

His deep awareness of of the human condition, rooted in resistance, permeated all his works. In A Grain of Wheat, Ngũgĩ stressed the importance of unity in resisting tyranny, “Our fathers fought bravely. But do you know the biggest weapon unleashed by the enemy against them? It was not the Maxim gun. It was division among them. Why? Because a people united in faith are stronger than the bomb.” He believed that solidarity was a more powerful weapon than any firearm.

In Petals of Blood, the author used striking symbolism to describe how imperialism operated under a seemingly noble guise. “He carried the Bible; the soldier carried the gun; the administrator and the settler carried the coin. Christianity, Commerce, Civilization: the Bible, the Coin, the Gun: Holy Trinity.”

When he was not exposing power structures, Ngũgĩ spared some time to ecourage personal and communal resistance. In a 2018 interview with The Guardian, he said: “Resistance is the best way of keeping alive. It can take even the smallest form of saying no to injustice. If you really think you’re right, you stick to your beliefs, and they help you to survive.”

On faith and the journey of becoming

In his 2010 memoir Dreams in a Time of War, the literary icon showed a somewhat softer side of himself when he wrote: “Belief in yourself is more important than endless worries of what others think of you. Value yourself and others will value you. Validation is best that comes from within.”

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Ngũgĩ believed that this inward journey was important for personal and political awakening. “Being is one thing; becoming aware of it is a point of arrival by an awakened consciousness and this involves a journey.” He observed in his 2013 Novel, In the Name of the Mother: Reflections on Writers and Empire.

Ngũgĩ’s courage extended beyond literature. His politically charged play I Will Marry When I Want, co-written with Ngũgĩ wa Mĩriĩ, was banned shortly after its 1977 premiere for criticizing government corruption and inequality. Despite censorship and imprisonment, Ngũgĩ never relented. The play remains a landmark in African theatre and a symbol of resistance.

Ngũgĩ fiercely championed for gender equality, frequently using his work to highlight the condition of women in society. “The condition of women in a nation is the real measure of its progress,” he stated in Wizard of the Crow. For him, the oppression of women weakened the entire fabric of society.

As Kenya—and the world—mourns the passing of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, his words remain etched in the conscience of generations. Through literature, he taught us that language is power, unity is strength, and justice is worth fighting for.