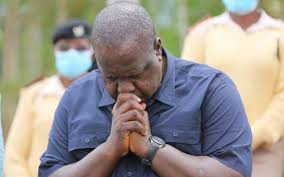

Earlier this week, Interior Cabinet Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen urged Kenyans to be patient with police officers who sometimes ask for fuel contributions when responding to emergencies.

Speaking at the Jukwaa la Usalama public engagement forum, Murkomen explained that each police station receives a capped allocation of 450 liters of fuel per month.

He noted that this allocation often runs out before the month ends, especially in urban areas where officers are more engaged in crime prevention.

“So please bear with the police officer if they ask you for fuel. It is not corruption or a demand for a bribe, it is simply a result of the current leasing program, which provides 450 liters per month,” Murkomen said.

While the CS’s remarks might have been meant as a simple explanation for why officers ask for “fuel money,” experts believe otherwise.

Transparency International Kenya (TI) told The Standard that asking for “fuel money” from citizens squarely qualifies as corruption.

According to TI, the Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act defines corruption as abuse of office, including bribery and fraud. The Bribery Act further states that offering or receiving money in exchange for an official function amounts to bribery.

In essence, TI says, asking for fuel money so police can carry out their lawful mandate is a form of corruption punishable under Kenyan law.

The Agency also pointed out that one of a cabinet secretary’s core responsibilities is to provide policy and strategic direction, and to strengthen institutions so they deliver effectively. Murkomen’s remarks, therefore, could be interpreted as legitimizing an illegal practice.

“The remarks by the Cabinet secretary would bring about a situation whereby the citizens would need to bribe the police as a matter of necessity in order for law enforcement authorities to perform their function, which is already classified as a crime in Part 2 of the Bribery Act.”

“Simply put, this is the normalization of a culture that has long been an open secret, and the remarks by CS Kipchumba Murkomen is an attempt to bring up to the surface an illegal practice that has long been an open secret in the police service in a bid to make it appear normal, whereas the same has been clearly categorised as a crime under the Kenyan law,” said TI.

TI further warned that such a precedent would mean access to justice is determined by a citizen’s ability to pay, undermining the Constitution and eroding the essence of government.

Amnesty International Kenya Director Irũngũ Houghton echoed the same concerns, noting that even if well-intentioned, Murkomen’s comments are unsettling for ordinary Kenyans, especially marginalized communities.

According to Houghton, many Kenyans are already coerced into paying bribes for services or to avoid harassment, and these remarks risk normalizing bribery in law enforcement.

“The comments have another risk of justifying services only when communities can pay for ‘fuel’. The Constitution of Kenya guarantees all citizens equal protection and fairness under the law. Justice cannot be transactional and left to a citizen’s ability or willingness to pay.”

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

“If this were to be allowed, 20 million Kenyans under the national poverty line who cannot afford to pay will be left vulnerable to neglect, abuse, or arbitrary arrest,” said Houghton.

He added: “The statement risks normalising bribery within law enforcement. It blurs the line between the real logistical challenges our officers face, criminal behaviour and the need for realistic budgeting for police services by the National Police Services, Executive and the National Assembly. Let neither citizen nor police officer misread the Cabinet Secretary’s statement as an invitation to exploit citizens under the guise of operational necessity.”

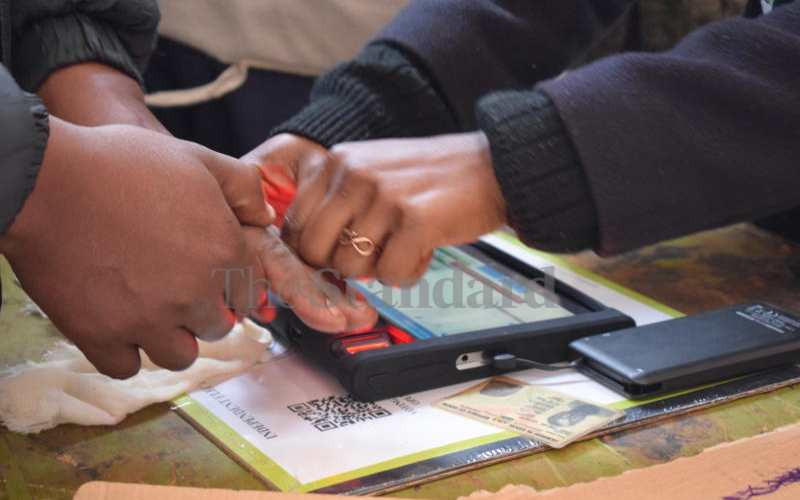

Findings from the Kenya Bribery Index 2025 back these concerns. The police ranked worst on the likelihood of bribery indicator, with a score of 72 percent, meaning 7 out of every 10 Kenyans who interacted with police faced a bribery situation.

On prevalence, the police again performed worst with a 51 percent score, indicating that in every two bribery situations involving the police, one citizen paid up. Notably, 40 percent of all bribes reported in the survey were paid to the police.

TI warns that legitimizing “fuel money” normalizes an already rampant vice. The Agency says it emboldens officers to demand bribes openly without fear of consequences, while eroding public trust in government institutions.

Houghton agrees: “They significantly damage public trust. Citizens pay taxes in the expectation that institutions like the police will impartially uphold the law and protect their rights. When leaders appear to excuse misconduct, it undermines confidence in the entire criminal justice system. Trust in “utumishi kwa wote” and not “utumishi kwa wale wanaoweza kulipa” is the cornerstone of effective policing.”

TI has called for a transparent, participatory budget-making process within the National Police Service, involving officers in identifying needs at various stations to ensure allocations are realistic.

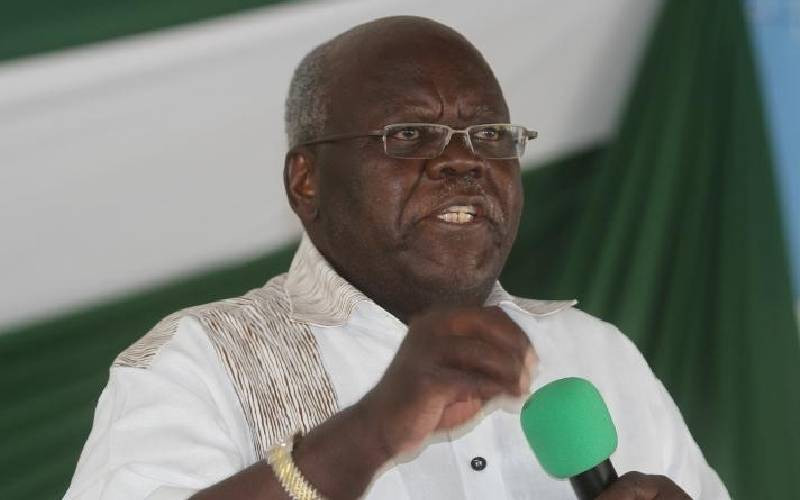

Governance lawyer Javas Bigambo also stressed the need for urgent policy reforms to close this loophole.

“When the CS said asking for fuel is not corruption, it begs the question of what happens when police exploit that gap. Some police may refrain from offering help because there is ‘no fuel’. And if it is not available, they may be reluctant to provide services. Therefore, it is high time the Ministry comes up with policies to seal that gap before some police exploit Murkomen’s statement and engage in mischief,” said Bigambo.

As the debate continues, the fear is that an endorsement like Murkomen’s would push access to justice further beyond the reach of struggling Kenyans, and entrench corruption deeper within a service that perennially ranks as Kenya’s most corrupt institution.