On Jamhuri Day earlier this month, when recounting successes of his government, President William Ruto said well over 243,000 Kenyans had secured jobs abroad since September 2022, when he was sworn into office.

The opportunities these Kenyans have taken up, he said, are mainly in healthcare, construction and agriculture. These jobs have predominantly been in Europe and in the Middle East.

This administration rode to power on the promise of, among many other things, solving rampant unemployment, a juggernaut which has inspired hopelessness, public ire and crime. Even early on, the prospect of Kenya earning hefty amounts from diaspora remittances, and potentially doubling this by 2027, had been discussed in earnest.

In 2023, testament to this pursuit, Kenya received a record $4.19 billion in diaspora remittances. While this was a 4 per cent increase from 2022, more was expected- the government envisaged $10 billion in about two years and more had to be done to reach that goal.

In its election manifesto, Kenya Kwanza outlined plans to revive the economy from the bottom up, ensuring even the least privileged in society were well taken care of and did not continue to experience a shortage of resources.

The manifesto, dubbed the Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (2022-2027), highlighted a serious underutilisation of the informal sector. “An estimated 10 million informal micro, small and medium entrepreneurs (MSME) operators and workers generate less than Sh5,000 income a month on average, which is below the living wage for one person,” the manifesto said.

“This is a reflection of the hostile environment they operate in, criminalisation of their enterprises (eg hawkers), as well as disguised unemployment. These 10 million people, who represent half of Kenya’s workforce, are the country’s most underutilised resource. Our estimates show if these workers were as productive as those in established SMEs, they would be generating Sh6 trillion a year, which is 60 per cent of GDP i.e., the economy would be 60 per cent larger.”

The government planned to help this group out of this situation by ending criminalisation of work, slamming brakes on regressive taxation, increasing access to finance, and prioritising infrastructure and capacity building.

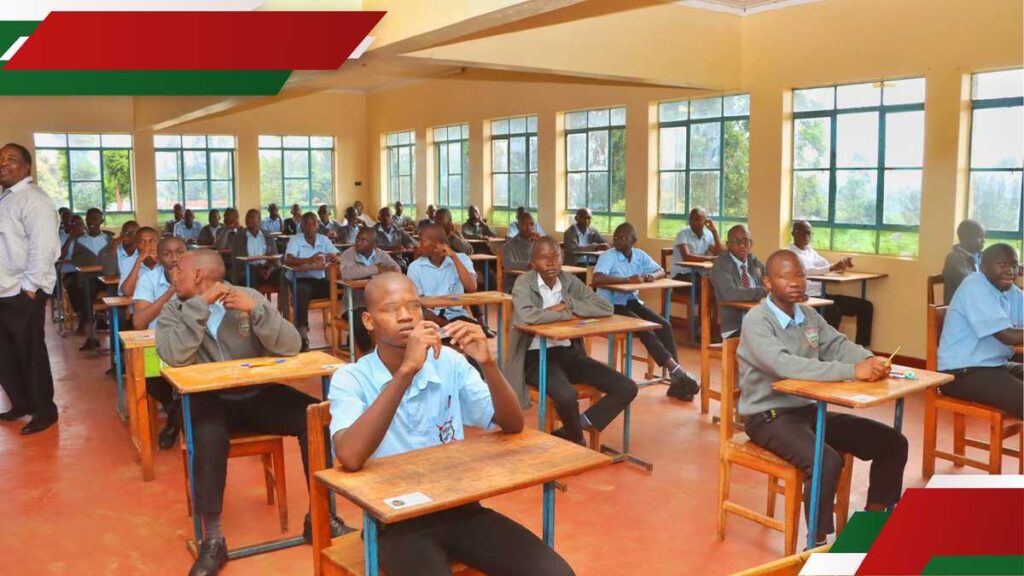

But part of the plan was to send labour abroad in markets that need it. The last available quarterly labour force report by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), which was for the last quarter of 2024, showed 4.9 per cent of Kenyans were unemployed. Of 18,371,526 youth, the report noted, there were 3,499,114 labeled as “Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET)”.

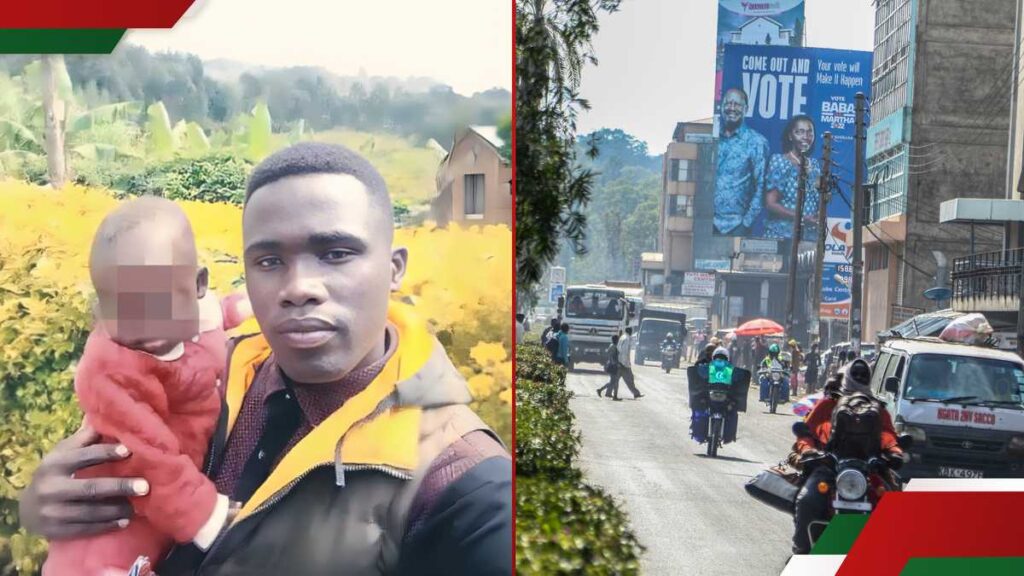

It is this group that have been mainly targeted for jobs the government continues to seek abroad, with the expectations that hundreds of thousands will benefit and, hopefully, invest back home. Due to the relentless pursuit of greener pastures abroad the Kenya Kwanza government, Kenya’s youth, the President says, are increasingly getting opportunities abroad. Locally or abroad, the youth need to be in productive activities.

They are the majority. The Kenya Population and Housing Census of 2019 showed that the country had over 18.4 million citizens aged between 7 and 22. They form the Gen Z group, which is getting into employment. The country had an additional 11.3 million people aged between 23 and 38. Their sheer numbers could make, or break, the country’s socio-economic fabric, and of late, even the political arena has felt the force of the youth.

Local resistance

To secure jobs for these energetic, trained and promising young people, the Ruto administration swung into action immediately after the election. In December 2023, Labour and Social Protection Cabinet Secretary Florence Bore said Kenya had signed a bilateral labour agreement with Saudi Arabia, in which graduate nurses could go work there starting January.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

This, however, faced local resistance. Kenya was already grappling with a shortage of medical staff, underpayment and late payment of nurses both of which have, in the past, caused serious standoffs and go-slows.

While that and many other deals signed promised better lives for Kenyans, the Germany one triggered widespread debate. An early 2023 meeting between German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and President Ruto led to a joint declaration that the yawning labour gap in Germany would be filled by Kenya’s skilled and semi-skilled labour.

On 13 September, when Ruto visited Berlin, he signed, with his counterpart Scholz, the Migration and Mobility Partnership deal.

250,000 Kenyans, Ruto said, would be departing for Germany. A joint implementation committee would expedite the transition. Soon, however, Germany’s Federal Ministry of Interior refuted the claims, insisting there were no numbers promised in the deal.

“All applicants must meet the strict requirements of the German Skilled Immigration Act,” the Foreign office wrote on its X account.

On social media, opponents and proponents of the deal were embroiled in a fierce war of words for days. The protesting Germans were joined by a host of Kenyans who were, themselves, unhappy with their government negotiating deals outside instead of creating opportunities locally.

On X, a number of Germans accounts expressed displeasure with the planned migration deal. One called it “biological warfare”. Another doubted the skills of immigrants “with an IQ of 70” which, according to 123 test means such persons are considered cognitively impaired. Others referred to the expected immigrants as “scumbags”.

There was a general feeling the government was shunning a responsibility to better conditions in Kenya, instead setting sights on diaspora remittances of citizens most of whom, in the past, had been forced to work under harsh conditions abroad. Germany’s population has grown increasingly skeptical of immigrants, having suffered high rates of illegal immigration in recent years. In 2023 alone, well about 100,000 people entered Germany illegally.

The Kenyan government has promised many other jobs and signed contracts with many other countries and institutions abroad.

The president also promised to have agreed with some organisations abroad to offer Kenyan youth remote jobs, and even said he had met with some locals who were already working online for foreign companies and making a fortune.

Recruitment agencies

In November, the National Youth Service announced 217 job opportunities for its graduates in Saudi Arabia. Some of these jobs were heavy equipment mechanics, heavy equipment electricians, generator technicians, and automotive AC technicians. The government then announced an agreement with Qatar, in which thousands were to leave for Doha. “During the first phase of the Qatar initiative, 3,247 Kenyans were selected out of the 8,000 available positions. I am pleased to report that nearly 1,500 of them have already received their offer letters and are finalising their travel documentation,” Labour Cabinet Secretary Alfred Mutua said.

With the promise of so many jobs abroad, sham recruitment agencies opened in dingy backyards.

In May, the government revoked over 700 licences for conniving agents. There were a number of instances where Kenyans paid money to recruitment agencies for lucrative jobs abroad but then got conned.

In an event to inaugurate the Kazi Majuu job fair in Meru, speaking in Meru, Foreign and Diaspora Affairs PS Roseline Njogu warned Kenyans against falling for these unscrupulous dealers.

She emphatically asked for them to always confirm to ensure that the National Employment Authority had registered agents they sought to use. Among the most sought-after workers in this category were housekeepers, DJs, cleaners, nurses, teachers, and barbers.

Mentoria Economics’ Chief Economist Ken Gichinga feels that the labour export could haunt the country in the long run. “From a broad perspective, it is neither a viable nor sustainable strategy, particularly for a country such as Kenya whose competitive advantage is in its human capital. Exporting its labour abroad could be detrimental in the long-run,” he says.

Gichinga, however, says that some of the youth securing jobs abroad might find a soft landing. If it may help kickstart careers and earn them a fortune, then good enough.

“But there are also those that might end up working in extremely harsh, challenging environments,” he says, regretting past incidents where Kenyans have found themselves in desperate situations.

Political analyst Javas Bigambo says globalisation should be appreciated with its opportunities and challenges. “When riding the horse of excellent diplomacy, nations open doors of opportunity for their countries for trade, military cooperation and opportunities for work for their citizens,” he says.

But governments “should provide information about the security and protection of Kenyans sent abroad to avoid the ever-worrying situation where domestic workers in the Emirates have suffered untold violations and enslavement in the hands of their employees,” he says.

“Opportunities abroad, which bring with them diaspora remittances, should come with assured security and protection for Kenyans,” Bigambo adds.