The year 2024 deserves to be called the Year of Africa. It has been a decade since the continent last experienced a surge of interest from the outside world, attracting the attention of major geopolitical actors and engaging in large-scale international events. The BRICS Summit held in South Africa late in August 2023 marked the beginning of an African renaissance after the pandemic-induced downturn that halted a quarter-century cycle of economic growth, setting the continent back at least 5 years and eroding much of the progress made in eradicating poverty.

Africa remains high on the global agenda in 2024, with the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation held in Beijing in September this year demonstrating the new aspirations of the leading geopolitical players. The Forum addressed a host of issues including governance, industrialization, agricultural modernization, global security and the development of cooperation. Thirty new infrastructure development projects were announced in key sectors such as transport and energy. What the world’s major powers export to Africa, however, is not limited to capital, technology, goods, weapons and military specialists.

Britain, China, France, and the US remain committed to educational projects and initiatives, which they implement through dedicated multinational foundations and in cooperation with local elites. The purpose of such initiatives is clear. Education serves as hardwiring that shapes the mindset of intellectual and political elites, inculcating values and views that the big players themselves espouse.

Moreover, an educated society is less prone to crime, violence, and terrorism, which reduces the problems and risks for investors pouring billions of dollars into infrastructure projects, mineral extraction, and the development of the energy and other sectors.

Russia also remains one of the top five countries whose degrees are highly valued in Africa as they give ordinary citizens and local elites a competitive edge.

Well, fair enough. The better educated local elites are, the easier it is for them to find common ground with the major geopolitical players, their leaders. This undoubtedly helps African countries to promote their interests and achieve development, which is well illustrated by the fact that Russia, or, more precisely, the Soviet Union provided Africa with a plethora of successful leaders and administrators.

Hosni Mubarak, who became president of Egypt in 1981 and led the largest Arab country for 30 years, was educated in the Soviet Union.

Hafez al-Assad, president of Syria from 1971 to 2000, graduated from the Soviet General Staff Academy.

Tabo Mbeki, who made a remarkable political career after the indigenous majority came to power in South Africa and served as the country’s president from 1997 to 2008, was also educated in the Soviet Union.

A “dynasty” of Soviet-trained leaders has run Angola. José Eduardo dos Santos was at the helm for 38 years after graduating from the Azerbaijan Oil and Chemistry Institute. He was succeeded in 2017 by president João Lourenço, who studied at the V. Lenin Military and Political Academy.Other prominent African graduates from Soviet universities include Yusuf Saleh Abbas, Prime Minister of Chad between 2008 and 2010; Antoine Somdah, Burkina Faso’s Ambassador to Russia; Jeanne d’Arc Mujawamariya, Rwanda’s Minister of Environment; Khalifa Haftar, Field Marshal and the 2021 presidential candidate.

There is, however, one subtle but important difference in the way Western countries and Russia have treated Africa’s young talent. Western countries have tended to focus on providing Africans with basic education, but if a young person shows potential for development, Western “partners” see him or her as a resource to be drained off to “the metropolis”. Of those Africans who have had the chance to study in England, France or the US, less than 5 per cent return home.

Russia, on the other hand, has taken a very different approach, following the tradition of the Soviet Union and encouraging students to return to their countries of origin upon graduation. Statistics show that from the early 1960s to 1990s, Soviet universities awarded degrees to more than 60,000 foreigners. Most of them studied manufacturing, agriculture, transport and social policy — areas vital to African development.

Thus, the West has been draining off African talent while Russia, by contrast, has been creating and channeling it into students’ own countries.

Indeed, Russian education remains in high demand. Russian universities have welcomed students from Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo. There are currently 35,000 such students in Russian universities. More than a quarter study for free.

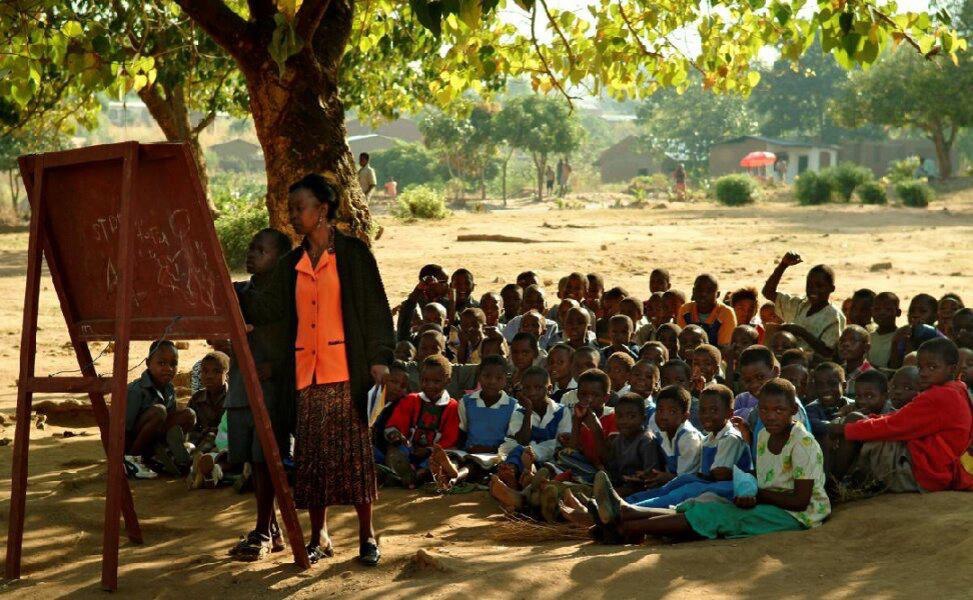

Today, African countries, more than others, need to critically reassess their education systems and the practice of “exporting” their students overseas. Legacy education systems inherited from the colonial era often remain intact under the pretext of preserving the quality of education. The result is that a small proportion of students — the elite — receive the same education as they would have received in Europe, while the vast majority of students either lack access to modern-day education or have to work for the same countries in which they were educated, after graduation. This is out of step with the times and needs to change.

Until 2040, a high fertility rate will undermine many of the gains made by African economies. There will be an influx of low-skilled migrants and unemployed youth into cities, posing a constant threat to social and political stability, while competition for land will intensify, especially in rural areas. In addition to the conflict zones in the Sahel (Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso), the Lake Chad region (Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad), the western part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and northern Mozambique, other hotbeds of tension are likely to emerge. Terrorism could spread to the Gulf of Guinea (Benin, Côte d’Ivoire) and the Swahili coast (Kenya, Tanzania), with the possibility of new pockets of instability in Nigeria and Cameroon.

These factors are important only for the African continent, but also for the major geopolitical players with interests in African countries. Rather than causing a “brain drain” from Africa, one should strengthen the stability of indigenous communities by fostering an educated and intelligent middle class that embodies civilized values.