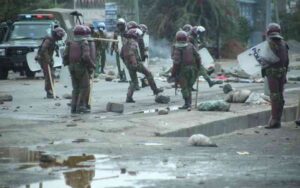

Kenya’s capital ground to a halt on Monday as police enforced an extraordinary lockdown, turning Nairobi’s normally bustling streets into empty corridors of roadblocks and riot police squads.

What was meant to be a day commemorating 35 years of the push for political space instead became a city under siege, sealed off at dawn by layers of security checkpoints and armoured vehicles.

Saba Saba, July 7, marks the anniversary of the 1990 demonstrations that challenged the single-party rule and ushered in multiparty democracy. But this July, the promise of that struggle felt distant as police choked off access to the Central Business District (CBD) and major roads, citing “orders from above.”

By early morning, Nairobi was a ghost town. Roads normally clogged with matatus, boda bodas, and hawkers lay silent behind barricades. Police in black armour checked IDs, turned away ambulances and essential workers, and waved aside pleas.

The city was cold, drizzling, deserted, dirty and eerie.

At Kipande Road, Jane, a Kenya Defence Forces soldier in civilian clothes, begged police to let her through.

People are providing essential services,” she urged.

“We were told no one should enter the city,” an officer replied.

Heavy checkpoints

Similar scenes played out across the city as thousands, those heading to work, those from as far as Western, Wajir and Mombasa, were stranded with luggage, children and travel exhaustion at various points citywide. On Kiambu Road alone, The Standard counted three heavy checkpoints before Muthaiga. At Ridgeways, uniformed police scrutinised every ID. Near AAR Hospital, plainclothes officers waved motorists aside. Men in jeans and boots gripped black rungus at the final barrier.

In the heart of Nairobi, Parliament Road and City Hall Way, usually packed with commuters, lay deserted, police guarding every entry and government installation, plainclothes officers patrolling while some in small saloon cars moved discreetly, taking photographs.

Despite the visible lockdown, Deputy Inspector General of Administration Police, Gilbert Masengeli, denied that anyone had been barred from entering the CBD.

Patrolling with senior officers, Masengeli told journalists at the University Way roundabout:

“We have been here, and everyone is allowed to enter the CBD. People are also reporting to work as usual.”

He urged protesters to remain peaceful: “I urge everyone to keep peace and confine themselves within the rule of law.”

Everywhere, security forces enforced a strict cordon. On Ngong Road, traffic ground to a halt near the City Mortuary, the first choke point in a long day of blockades. Valley Road was sealed at the Department of Defence, another early barrier. State House Road was blocked tight at Integrity Centre, part of the first defensive ring.

Uhuru Highway was closed at Haile Selassie Roundabout. Mombasa Road was cut off at General Motors. Thika Road was impassable at Roysambu, Allsops and Pangani. Waiyaki Way was shut down at the Kangemi Flyover.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Meanwhile, every entrance into the CBD bristled with reinforced roadblocks. Teams of officers stopped cars, demanded IDs, and turned back essential workers—no exceptions, no explanations. And even if you slipped past the first barriers, more awaited. Layer upon layer of checkpoints blocked anyone from entering or leaving town. “I worked throughout the night and was expecting to get home to sleep and rest. I am here, worn out and fearing for my life,” said Maureen Akinyi, a chef at a city hotel stranded along Tom Mboya Street.

Fear of undercover squads

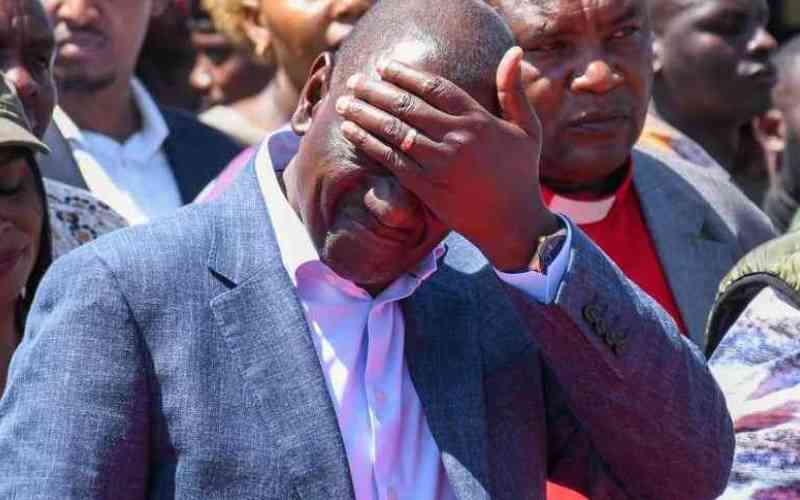

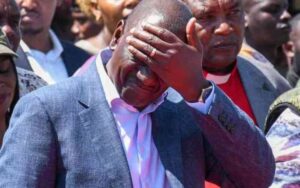

The military and GSU stood watch in their camps. Unmoving. It was a show of the power of the gun, clear, unblinking, signalling that President William Ruto was in charge and had no intention of listening to Kenyans angered by what they called bad leadership, lost jobs, crumbling public services, and deeply unpopular policies.

For some, the chaos was an opportunity. James Mumo, a boda boda rider, charged passengers Sh300 to sneak into town.

“Tunajua hii town na hawawezi funga yote,” he said with a grin.

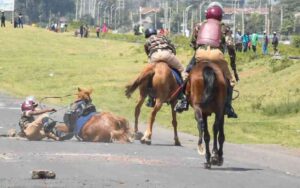

But police adapted. At Globe Roundabout, Haile Selassie and within the CBD, officers tackled riders off their bikes, loaded them onto trucks, and arrested them.

The city’s lockdown also brought fear of Kenya’s dreaded undercover units, which human rights groups have documented as responsible for tens of people missing, hundreds injured, and others killed.

Unmarked Subaru Foresters cruised through estates, occupants in jeans and baseball caps pulled low.

“They all looked dirty, unsettled, and dangerous,” said a commuter near Jeevanjee Gardens.

Small Toyotas, Vitzes, Voxys, and pickups roamed filming intersections and crowds.

“Our job is to take videos and send them,” explained an officer in a dusty white Toyota on Kimathi Street.

The clampdown was methodical. Kiambu Road alone had three main checkpoints: Ridgeways (uniformed police), near AAR Hospital (mixed plainclothes and uniformed), and Muthaiga (plainclothes with black fungus).

Similar setups sealed off Ngong Road at the City Mortuary, Valley Road at the Department of Defence, State House Road at Integrity Centre, and the main highways leading into town.

Inside the city, shops were shuttered. Schools closed. Riot police patrolled in armoured trucks, watching silent lines of people forced to walk. And plainclothes officers remained scattered across the streets holding various positions.

Beyond Nairobi, protests flared on highways with burning tyres and plumes of black smoke.

National clampdown

On Sunday night, police stopped buses at Mombasa’s Dongo Kundu Bypass, accusing youths of attempting to travel to the capital after the Summer Tides Festival in Diani. Kenya Railways cancelled its 10 pm night train from Mombasa to Nairobi, stranding hundreds. The official reason is a “technical fault.” “They don’t want anyone coming to Nairobi,” said a frustrated passenger at Miritini Station.

Long-distance buses were parked at Kabete Police Station. Passengers waited helplessly. In Gitaru on Waiyaki Way, youths lit fires to block traffic. Police fired tear gas in response.

“They want to stop us even from saying how hungry we are,” said Odhiambo Martin in Dandora.

“Saba Saba was supposed to be our day to speak,” said a young activist in Eastlands. “Now they have turned Nairobi into a military camp.”

President William Ruto’s commitment to democracy remains contested. A veteran of Kanu, he voted against the 2010 Constitution designed to curb presidential power. Critics say checks and balances have since eroded.

Even before the protest, his government labelled demonstrators “goons” and “treasonous.” “They’re afraid of the people. They’re afraid of anger about taxes, corruption, and police killings,” said a human rights lawyer.

As light rain fell, Nairobi’s roads filled with puddles. Police huddled under umbrellas, watching soaked commuters walk kilometres home.

By dusk, the city remained sealed. Shops stayed shut. Schools closed their gates. Police convoys continued slow patrols through silent neighbourhoods. Even as night fell, tension buzzed like a live wire. “They might stop us today, but Saba Saba is an idea. They can’t kill that,” the Eastlands activist said.