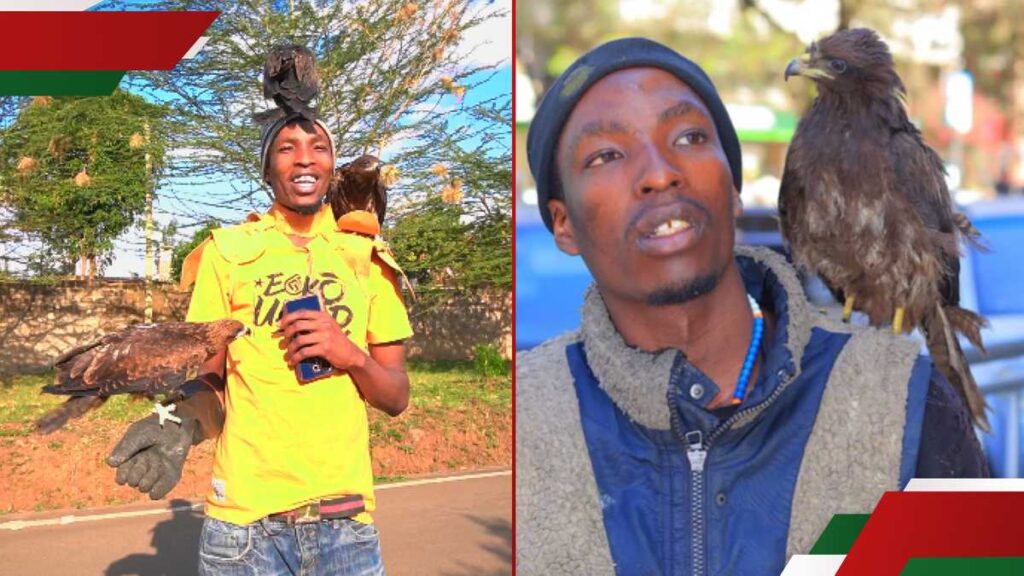

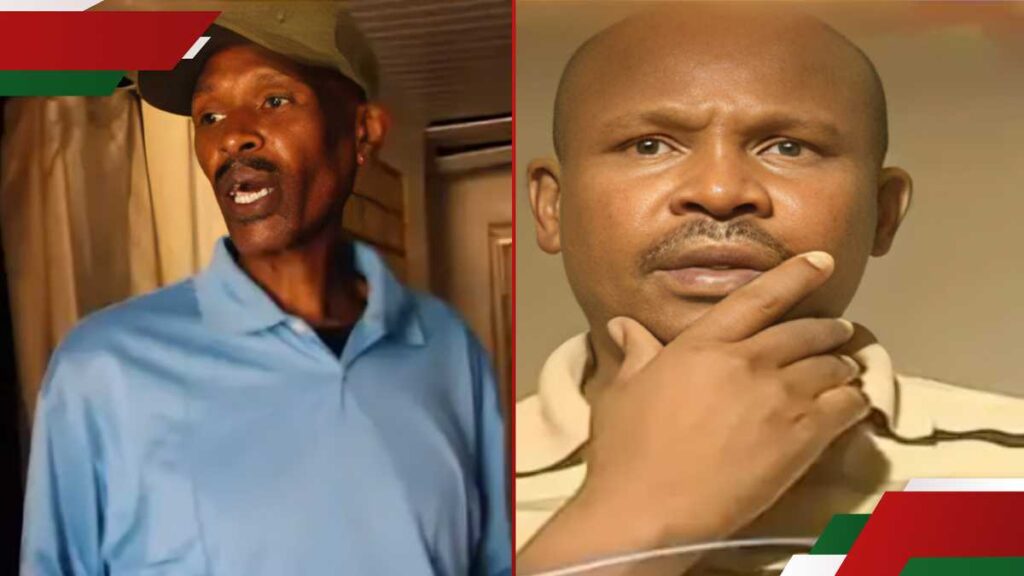

Daniel Ndirangu was at the right place; his town, his job, his routine. But June 25, 2024 turned out to be the wrong day.

The matatu tout in Nyeri town, was used to daily rhythm of chaos; shouting for passengers, loading luggage, navigating impatient drivers and narrow streets. But on that Tuesday morning, he wasn’t on his usual route.

The roads had been rendered impassable by swelling protests led by Gen Z, young people rising up against corruption, taxation, and a political system that had failed them for decades.

But Ndirangu, 37, wasn’t among them. He wasn’t protesting. He was delivering a parcel for a customer, on foot, because no matatus could get through. As he turned a corner near Chieni supermarket, everything changed.

“I just saw a huge crowd rushing toward me. They pushed me and I fell,” he recalled.

“Before I could move, I heard loud bangs of teargas, maybe even gunshots. I was confused,” Ndirangu told The Standard.

In a flash of smoke and panic, people were screaming, running, stumbling. Police in riot gear unleashed a barrage of teargas and bullets.

Ndirangu turned to escape. But within seconds, his left leg collapsed beneath him. He hadn’t seen the bullet; he didn’t hear it. He crashed to the ground.

He had been shot twice on his left leg. “All I knew was that I couldn’t move. My leg felt numb. It felt like a sting. I rolled my trousers to check my leg and blood was pouring out,” he narrated.

For minutes that felt like hours, he lay on the ground, shocked and silent, as people surged past him. He could have bled out there, alone on the street. But then, he heard voices of protesters.

“Someone said, ‘We can’t watch someone bleed to death. Call Red Cross.’ That’s the last thing I remember before I blacked out,” he narrated.

He woke up at Nyeri General Hospital where he was taken to theatre for an operation. He was groggy and disoriented. He was in more pain than he had ever known.

“I didn’t even know what had happened. I thought they would fix my leg. I didn’t think I would lose it,” he said.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

After the surgery, doctors delivered the sad news that the bullet had shattered the bones, and the gunpowder contamination had begun to spread.

After eight days of trying to salvage what they could, they told him the leg had to go. There was no other way. The infection was worsening. The other leg, they warned, could also be affected.

But Daniel couldn’t accept it. Not at first. Not when the cost of surviving meant losing the very thing that helped him earn a living, his body in perfect shape.

“Initially they said we give it eight days before amputating. I insisted that my leg would not be cut. I told my family to take me to a hospital that could treat me without losing my leg,” he said.

After the lapse of the 8-day grace period, He had not changed his mind. He did not want to lose his leg. He pushed it to two more weeks.

But his leg began to decay. The smell, the pain, the swelling, there was no choice left. He signed the consent form. When he awoke again, his left leg was gone. Gone too was the life he knew.

He was no longer able to stand in the matatu stage, no longer able to jump in and out of moving vehicles, no longer able to chase after passengers or carry loads, Ndirangu was now a man forced to rely on others.

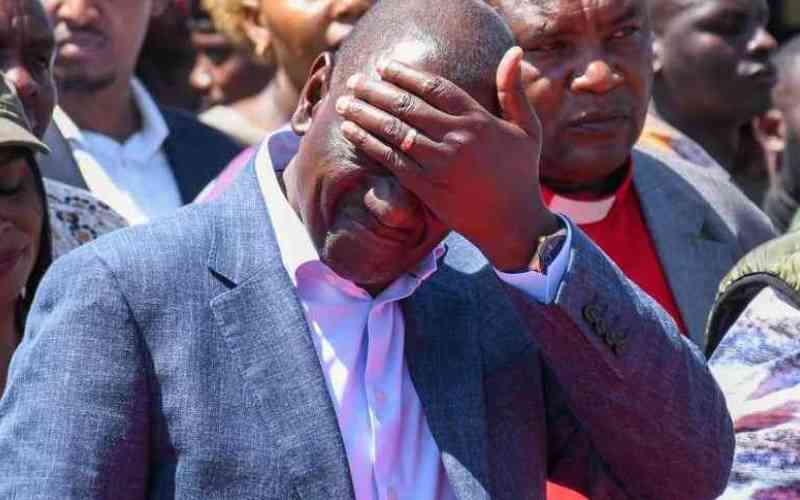

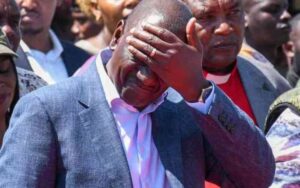

“The sight of me without one leg shattered me. I cried the whole night. I hated myself. I was in denial. I kept asking myself, how can I lose a leg for something I wasn’t even part of?” he posed.

His wife, a salonist, became his caregiver. Seven months pregnant at the time of the incident, she carried both her unborn child and the weight of a family in crisis.

Their two children watched as their father, once the breadwinner, the strong one, sank into silence, then into despair. “I lost all confidence. I hated myself. I felt like a burden,” Ndirangu said.

“What pains me the most is seeing other men working to provide for their families, seeing my former workmates doing the job and I cannot do it myself. I feel so useless,” he said.

There are days Ndirangu wishes he had stayed in bed that morning. He hadn’t even planned to work on the material day. He had told his wife he felt too tired, that he would stay home and rest.

But when he realised she was already out of the house, on her way to work, pregnant, he changed his mind.

“I thought, how can I stay home while my pregnant wife goes to work? I thought it would be lazy of me. But I wish I had listened to my intuition and stayed at home,” he regretted.

Now, he lives with regret, rage and fear. A glimpse of a police officer, the sight of a gun, is a painful trigger of pain and bitterness. He says it’s like being shot all over again, only this time it’s inside his head.

“I have thought of committing suicide several times. I feel useless. I wish they had just killed me because it could have just ended at that. But being in this condition made my life miserable.”

“My friends deserted me and everyone I talk to thinks I am begging,” he said.

However, oversight bodies like the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA) have not conducted investigations. A year later, no prosecution was done against the officers accountable for the injuries.

A year later Ndirangu’s repeated attempts to seek justice through the Ipoa offices in Nyeri have been met with delays and inaction. At first, he reported and he was promised that he would be called. No one followed up. The second time, he was told the person who could help him was unavailable.

And like many victims who faced similar hurdles of lengthy bureaucratic processes and a lack of transparency that obstruct their quest for accountability and justice, Ndirangu gave up following up.

And yet, despite it all, the father of three holds on to one hope, that with the help of well-wishers, he might receive a prosthetic leg. That one day, he will walk again. Work again. Live well again.

“I just want to fend for my family with dignity because that’s what keeps me going,” he added.

IPOA chairman Isack Hassan blamed the police for non-cooperation during investigations. “The police force has not yet accepted a civilian body oversight, and we still have a long way to go. Most of them do not want to cooperate,” said Hassan.

He spoke during the airing of a documentary titled Last Catch, a reenactment story of a fisherman was shot dead by police and his friend falsely charged. The film was produced by International Justice Mission (IJM).

“The police only cooperate in cases that have drawn public interest and viral stories, like the recent cases of Albert Ojwang and Boniface Kariuki. But as soon as the heat reduces, they go back to factory settings,” he added.

Hassan said for Ipoa investigators to get access to documents within the police station, they have to get clearance from Vigilance House, the Police Headquarters.

Hassan said the agency required more support for ease of work. “Ipoa has around 280 staff countrywide. They are also required to serve about 125,000 police officers. Remember, we only have eight regional offices, and only 77 investigators to cover 1,200 police stations. We are overstretched and over-burdened,” said the Ipoa boss.

Ndirangu is one of many Kenyans caught in the chaotic events of June 25. His story is not just one of loss, but a story of injustice, survival, and of a Kenyan whose only mistake was getting up to go to work.

He is among more than 600 people who were injured during the countrywide anti-government protests. A generation expressing frustrations and demanding change was met with heavy-handed policing.

Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, last year, reported that between June 18 to July 1, 2024, 610 cases of injuries sustained by protestors, ranging from deep fractures, bullet wounds, soft tissue injuries, and inhalation of tear gas.

The commission also documented 1,376 arbitrary arrests. “Most of the injuries were inflicted by the security officers against the protestors. The Commission also documented 25 injuries inflicted on security officers by the protestors,” said the commission’s vice chairperson, Raymond Nyeris.

Although there are compensation schemes, they are poorly publicised and difficult to access.

And for the physical and psychological scars borne by victims like Ndirangu are a stark reminder of the urgent need for reform in how police should handle protests and compensation for the victims.

“My message to the police officer who shot me is that you wronged me. You robbed me of my livelihood and handed me a disability. It pains me because I was not part of the protests,” Ndirangu said.